Any company that has $100 billion in cash and marketable securities on its books, as Apple does, is charging excessive prices for its products, in the sense of prices higher than necessary to make everyone at Apple ready, willing, and able to continue to do the excellent job that they are doing.

Is that a problem? Unfortunately, yes, for any society that’s supposed to be a thing of the people. It means that Apple is bilking the public: taking more from the people for their iPhones and Macbooks than is strictly necessary to give Apple an incentive to produce iPhones and Macbooks.

You don’t need the money to reward investors. Otherwise you would have paid the money out already.

You don’t need the money to build more factories. Otherwise you would have built the factories already.

You don’t need the money to pay Tim Cook. Otherwise you would have upped his compensation already.

And with an AA+ credit rating, you don’t need the money for an emergency either, since it would cost you almost nothing to borrow cash in a pinch.

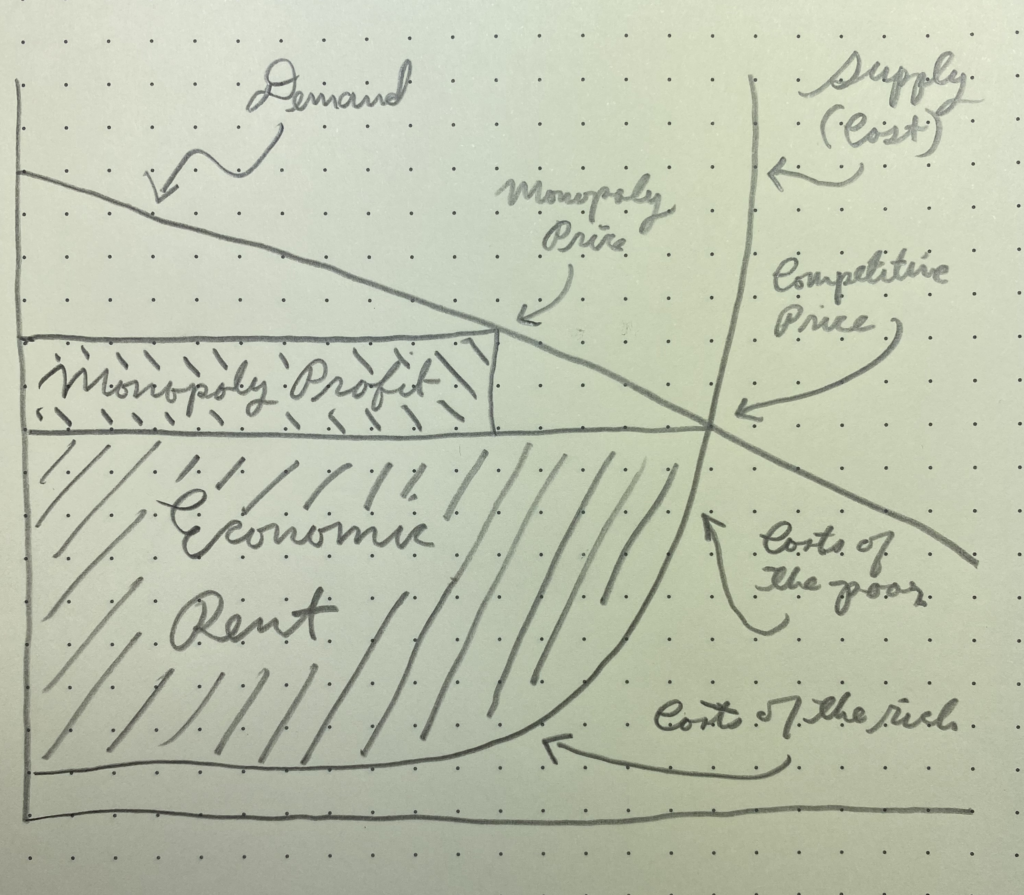

You just don’t need those billions, which is why they are what economists call “rents:” earnings in excess of what would be necessary to make the company, and all those who contribute to its success, ready, willing, and able to carry on.

Should government do something about these rents?

Yes. But not with the antitrust laws. Because Apple’s rents are not monopoly rents. Those are the excessive returns that come from making your products stand out by trashing your competitors’ products, rather than improving your own. Antitrust prohibits that sort of behavior.

But does anyone think Apple achieved the ability to charge $1,200 for an iPhone by making Samsung products worse?

Of course not.

Which is why there is no antitrust case against Apple.

Instead, Apple’s rents are Schumpeterian: excessive returns that come from making your products stand out by improving them, rather than by trashing the products of competitors. Antitrust does not prohibit such conduct.

Nor should it, because antitrust is a slayer, breaking up the firms that run afoul of its rules, saddling them with behavioral injunctions, and taxing them with trebled damages.

Those remedies make sense when the target is a firm that has gotten ahead by trashing competitors. That sort of firm doesn’t have a better product to offer, so smashing it is no great loss to society.

That’s not true for firms like Apple that have gotten ahead by being better. Smash Apple and you might well get Apple’s prices down. But you might also end up with poorer-quality products.

Why is it that Samsung keeps churning out gimmicky phones that are just a bit too ahead of their time to work properly, whereas, iteration after iteration, Apple phones continue to please?

Who knows?

By the same token, who knows whether Apple divided two ways, three ways or four ways will still have the same old magic? Organizations are mysterious things and we should break them only when they are already broken.

That doesn’t mean that something shouldn’t be done about Apple’s prices. As is so often the case, the right approach is the most direct: tell Apple to lower them.

There’s nothing novel about doing that. It’s the way America often has dealt with high-tech firms that get carried away with their own success. It happened with the landline telephone: the states regulated telephone rates for a century, and many retain the statutory authority to do so today. No vast cultural leap would be required to regulate the prices of iPhones or other Apple products.

Regulating prices runs much less of a risk of killing the golden goose, because it’s a scalpel to antitrust’s hammer, ordering prices down without smashing the firms that charge them.

But are prices really all that Apple’s antitrust adversaries care about? I think so.

The antitrust complaint brought by Fortnite-videogame-maker Epic is admirably transparent on this score, inveighing against what it calls Apple’s “30% tax” on paid App Store apps.

True, Epic spends a lot of time arguing that Apple should stop vetting the apps that can be installed on iPhones and should also stop requiring apps to accept payments via Apple’s own systems.

But it’s hard to believe Epic really cares whether consumers can run any app they want on the iPhone, or whether consumers can make in-app purchases with Paypal instead of Apple Pay.

The real reason Epic targets app vetting and payment systems lockdown is more likely because these two Apple policies prevent Epic from doing an end run around Apple’s 30% fee by connecting directly with users.

So to use antitrust to attack Apple’s prices, Epic ends up trying to thrust a stake through the streamlined, curated environment that iPhone users love. Needless to say, we know what a platform on which you can install anything and pay in any manner looks like: it’s called the PC, that bug-ridden, bloatware-filled, hackable free-for-all from which Apple users have been running screaming for decades now.

The beauty of price regulation is that you don’t need to redesign products to get what you want. Under price regulation, Apple would be able to continue to vet apps and manage payments, and thereby maintain the experience its customers love. All the company would need to do is lower its prices.

Epic isn’t the only organization out to exploit the antitrust laws for the sake of a bit of price regulation by least efficient means. Today’s Neo Brandeisians seem to share this goal.

That is the substance of an extraordinary piece by two affiliates of the Open Markets Institute that calls for using antitrust to smash big firms, but allowing small firms to form price-fixing cartels. The idea is to redistribute wealth by reducing the prices big firms can charge and increasing the prices that the little guy can charge.

That sounds great. But why not just regulate prices directly instead of smashing the country’s patrimony to get there?

Indeed, I’m mystified by the contempt in which this supposedly-radical movement seems to hold price regulation. The movement is all for returning to antitrust’s New Deal heyday. But it has nary a word to spare for price regulation, which was a much bigger part of the New Deal and the mid-century economic settlement that followed it, during which fully 25% of the American economy by GDP was price regulated.

One wonders whether the Neo Brandeisians share the Chicago School’s old concerns about “capture.” Something tells me they might.

Nevermind that we learned long ago that the notion that administrative agencies are captured by those they regulate is too simple by half.

And no one has been able to explain to me why the judges who apply the antitrust laws are any less susceptible to capture than are government price regulators.

But I do know that most Americans don’t seem to know that their gas, electricity, and insurance rates are regulated by government agencies, which says a lot about whether price regulation is the supreme evil that antitrusters of all stripes make it out to be.

The Neo Brandeisians’ mania for competition is really just run-of-the-mill American anti-statism, with a bit of progressive polish. Consider another example of intemperate fervor for competition, one that differs from the Neo Brandeisians’ campaign against big tech only in lacking that campaign’s radical pretensions: The Hatch-Waxman Act.

Rather than follow the rest of the world in regulating prescription drug prices directly, the United States has chosen to use competition from generic drugs to drive down drug prices after patents expire. The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 was meant to kickstart the plan by streamlining the generic drug approval process.

It’s important to understand how ridiculous using competition to reduce off-patent drug prices really is. Far and away the greatest virtue of competition is that it leads to innovation: firms must make better products or lose out to competitors.

But when it comes to generic drugs, competition cannot lead to innovation, because generic drugs are by definition copies of old drugs!

If a generic drug company were to innovate in order to get ahead of its competitors, its product would need to go through full-blown clinical trials in order to receive FDA approval and would also likely receive patent protection, instantaneously removing it from the competitive generic drug market and driving up its price. So the innovation rationale for competition just doesn’t exist in the context of generics.

But we decided to promote competition anyway, purely for the purpose of reducing off-patent drug prices.

It kind of worked.

Prices for many off-patent drugs fell. But not for all off-patent drugs. As scandals involving Daraprim (of pharma bro fame) and the Epipen show (the latter in the device context), it turned out that competition does not always come to the rescue once patents expire and regulatory hurdles are lowered.

More importantly, the cost of maintaining the system turned out to be immense. Firms responded by finding ways to prevent their drugs from going off-patent, leading to interminable patent and antitrust litigation. Just google “reverse payment patent settlements”–one of the mechanisms used by drug makers to undermine competition–and behold the flood of ink spilt on this avoidable disaster.

Worse, we have learned in recent years that generic drug quality is actually pretty terrible, even dangerous: competition is killing the golden goose.

Not, in this case, because Hatch-Waxman led to the break-up of big firms, but because when competition is just about getting prices down, firms will skimp on production costs. Ruinously low prices are, incidentally, supposed to be another of the great problems with price regulation–that regulators will dictate prices that are too low to cover costs–but it turns out that competition is at least as good at undershooting.

So what we could have gotten from a rate regulator in four little words–“lower your damn prices”–Hatch-Waxman accomplished in a patchwork way, at the cost of interminable litigation and sketchy pills.

Which leads me to ask: can Congress please do something about Apple’s $100 billion cash pile? How about putting aside $25 billion (just to make sure Apple has a nice cushion against shocks), and then rebating the other $75 billion to everyone who has ever bought an Apple product, pro rata? You can be sure Apple knows who they are.

And while Congress is at it, they can take a look at Microsoft and Alphabet, too.

For $100 billion is not actually the largest hoard in Silicon Valley.