Is the current inflation caused by corporate greed?

The answer is very likely yes.

But is it caused by monopoly?

The answer is very likely no.

The difference between these two answers tells us a great deal about why progressives should take an inframarginalist approach to political economy rather than an antimonopoly approach.

That is, it tells us why focusing on who gets the surplus generated by production is more helpful for progressives than obsessing about market concentration.

To see why the present inflation is likely about greed but not monopoly, we need to spend some time thinking about the concept of inflation, and, in particular, distinguishing between the inflationary spiral itself and the triggers of that spiral.

The Inflationary Spiral

As Olivier Blanchard pointed out a few months ago, inflation itself is a spiral, or a tug of war, bred of a conflict over the distribution of wealth.

In inframarginalist terms, it is a conflict over the distribution of surplus.

When a firm produces a good at a cost of $3 and sells it to a consumer who is willing to pay at most $7 for it, production generates a surplus of $4. The price the consumer pays divides that surplus between buyer and seller. If the price is $6, for example, then the seller gets $3 of the surplus (which we call “profit” in the economic sense) and the buyer gets $1 of the surplus.

The price suppliers charge the firm divides the firm’s share of surplus (i.e., divides the firm’s profit) between suppliers and the firm. If a supplier raises its price by $1, then the firm’s costs increase from $3 to $4, and its profits fall from $3 to $2. By raising its price, the supplier has redistributed one dollar of surplus from the firm to itself.

In an inflation, suppliers and the firm battle over the division of profits—they fight over price—but the battle gets out of hand because the battle isn’t just between one firm and its suppliers but between many firms and many suppliers. As a result, price increases by suppliers feed back into the willingness of consumers to pay the firm for its products, and that enables the firm to increase its own prices and profit levels in response to changes in supply prices.

Indeed, the economy is a great feedback loop. Rarely do a particular firm’s suppliers find themselves buying all of their own inputs from supply chains leading back to that firm. Firms sell to other firms’ suppliers and other firms sell to their suppliers.

But when we consider a large enough cross section of firms, it is the case that those firms ultimately sell to their own suppliers as a group. The economy is a tangled web, and although individual strands rarely loop back on themselves, the web as a whole does loop back.

Consider that $1 supplier price increase again. The firm might not be happy to lose $1 of profit. In order to make up for the loss of that dollar to suppliers, the firm might, in response, raise the price it charges to consumers. That would allow the firm to appropriate an additional dollar from consumers as a substitute for the dollar of profit that the firm lost to the supplier price increase. The firm might therefore raise price from $6 to $7, reducing consumers’ surplus from $1 to $0 (recall that the maximum consumers were willing to pay for the firm’s output was $7).

If the supply price increase is limited to this one market, and this one firm responds by increasing its own price, then the analysis ends here. Consumers will be made worse off; suppliers will be made better off; and the firm’s fortunes will remain unchanged.

But if many suppliers have increased their prices, and many firms have responded by increasing their own, then the firms’ price increase will feed back through the tangled web of supply chains that is the economy—back to the suppliers from which the firms buy.

Suppliers will find that the price of the inputs they need to buy to create the products that they supply to firms has increased. In our example, after the firm increases price from $6 to $7, the firm’s suppliers will now find that their own costs have increased by $1. The consumers who purchased goods from the firm for $7 instead of $6 will have increased the prices they in turn charge for the goods and services that they supply to others. And those others will in turn have increased their prices, and the price increase will have propagated through the tangled, looping web until it at last reached the firm’s own suppliers, who will experience it as an increase in the price of the inputs they purchase to make the things that they supply to the firm. Their input costs will increase by $1. (In reality, the a $1 increase in a supply price is unlikely to feed back into a $1 increase in costs, but a one-for-one feedback loop will do for a simple numerical example such as this.)

The $1 in extra input costs that the firm’s suppliers now incur will eat up the extra dollar of surplus they appropriated via their initial supply price increase. The extra dollar they charged to the firm will have turned out to be an extra dollar charged to themselves.

If suppliers want to preserve the extra dollar of surplus that they initially gained from the supply price increase, they will need to raise the supply price they charge to the firm again by another dollar. So suppliers raise price by an extra dollar. That price increase in turn redistributes to suppliers the additional dollar of surplus that the firm had appropriated from consumers by raising the firm’s price to $7 from $6. The firm now pays a supply price of $5 (the initial supply price was $3 and suppliers have now twice raised price by a $1) and once again takes only $2 of the surplus.

If the firm wishes again to make up for this reduction in profits, the firm must again raise its own price to consumers. But isn’t that impossible, because price is already $7 and the maximum that consumers are willing to pay is $7?

The answer is no. The willingness of consumers to pay has now risen from $7 to $8. Why? Because when consumers passed the firm’s original price increase of $1 on to suppliers, they effectively generated an additional dollar of income for themselves when they responded by raising the prices they charged to others. That additional dollar of income made it possible for them to pay an additional dollar for the firm’s product. Their willingness to pay went up.

(Note that consumers here can be individual persons, for whom the good is an input into their production of labor services. Or they can be other firms that produce other goods or services that eventually serve as inputs into the production of the supplies that the firm needs to make its own good. So when I say that consumers responded to the firm’s price increase by raising the prices they charge to others, I mean that they either demanded higher wages (in the case of consumers who are workers) or charged higher prices for the goods or services that they produce (in the case of “consumers” that themselves are firms).)

The firm therefore has leeway to raise price to $8 and the firm will do that if it wishes to restore its erstwhile profit level of $3. So altogether we have seen that an initial price increase of $1 by suppliers triggered a $1 price increase by the firm, which then triggered a subsequent $1 price increase by suppliers, which then triggered a subsequent $1 price increase by the firm. This cycle of price increases can continue for a long time.

That is the inflationary spiral.

In other words, the lines in Blanchard’s struggle over the distribution of surplus are drawn as follows.

On one side, you have a firm’s suppliers seeking to obtain a greater share of the surplus generated by the firm.

On the other side, you have the firm itself seeking to obtain a greater share of the surplus that it generates.

Firms and their suppliers can’t both obtain a greater share of the surplus. Suppliers raise prices, reducing firms’ share of the surplus. Firms then raise prices, seeking to recoup what they have lost.

As a result, the higher prices that firms charge eventually raise the costs of the firms’ suppliers, reducing their share of the surplus and leading them again to raise the prices they charge to firms. Firms respond by raising their prices again, and so prices rise and rise.

The Triggers of That Spiral

Ideas

Inflation spirals when suppliers and firms disagree over the proper division of the surplus. If there were no disagreement, the spiral would not get under way. Suppliers would raise prices to the point at which they would achieve the agreed surplus and firms would not respond, because they would be in agreement with suppliers that the resulting distribution of surplus is fair.

If the firm in our example were satisfied with $2 of profit, the firm would not respond to the supplier’s initial $1 price increase by raising its own prices by a dollar. The firm would eat the loss. And if all firms were to respond in this manner, then inflation would not ensue.

But, by the same token, because the heart of the spiral is a disagreement regarding what a fair distribution of surplus should be, an inflationary spiral can, in principle, develop at any time. And it can develop for what an economist might be surprised to discover are purely intellectual—indeed, even ideological—reasons.

If some cross section of America’s businessmen were to wake up one morning feeling that they are not getting a fair share of the surplus, and if they were to raise prices accordingly, and if their suppliers were to be unwilling to accept the smaller share of the surplus allocated to them by those higher prices, and if their suppliers were therefore to raise prices themselves, then we would be off to the inflation races.

This rarely happens, however, because the feedback loop only appears in the aggregate. Many minds would need to change at the same time. So if one supplier were to wake up and want more, that is not likely to lead to an inflationary spiral.

Indeed, if the supplier operates in a competitive market, the supplier might not even be able to raise prices, as competitors would simply take the supplier’s market share and the supplier would not be able to sell at all at higher prices. But if many suppliers were to wake up and want more, inflation would follow—if firms decide to contest this change by raising prices themselves.

Note that the distinction I have been drawing between a firm and its suppliers is arbitrary, because an economy is a feedback loop. At whatever level of a supply chain one wishes to focus—at whatever point along the loop—the focal point contains the firms of interest and the firms and workers that sell to them are the firms’ suppliers.

Given that mass shifts in views regarding the proper distribution of wealth are not common, and that the current inflation does not seem to be driven by one, we need to look for this inflation’s causes elsewhere.

Structure

Inflation that isn’t triggered by an ideological shift must be triggered by a structural change in the economy—a change that is broad enough in effect to cause many firms to raise their prices at the same time. Something must have happened to markets that gave one side of the conflict—suppliers or firms—the opportunity to take a larger share of the surplus, and the other side must have fought back by raising prices itself, leading to a tug of war.

Here is where the conflict between inframarginalism and antimonopolism comes into play.

The Antimonopoly Story: Crises Desensitized Consumers to Price Increases

Antimonopolists want to say that monopolies triggered the present inflation by using their monopoly power to raise prices.

If we imagine that the firm in our example is a monopoly, then antimonopolists want to argue that in 2021, when the present inflation started, this firm took the initiative to raise price from $6 to $7. Assuming that many other monopolies raised their prices as well, a feedback loop would have followed. Consumers would have passed the cost of the price increase on through the supply chain to the monopolists’ suppliers, which would in turn have raised prices by a $1, and then the monopolies would have responded by raising prices again by a dollar in order to hang on to the gains from their initial price increase. Consumers would have been able to pay that additional dollar because of the extra income they generated from passing on the original price increase. The inflationary spiral that appears to still be running today would have followed.

But this argument falls victim to the venerable question: why now? Antimonopolists themselves have argued that markets have been growing more concentrated for decades. They date the commencement of the trend toward concentration to the importation of Chicago School thinking into antitrust during the Carter and Reagan Administrations. If markets have been concentrating for decades, why would firms have waited until 2021 to raise prices and trigger an inflation?

Antimonopolists’ answer has been to argue that firms could not exploit market concentration to raise prices until the pandemic and the Ukraine war created the circumstances that would allow them to do so. To understand their argument, a trip through the mainstream economic account of the present inflation is required.

Mainstream economists argue that the present inflation was triggered by two structural factors: first, supply chain disruption triggered by the pandemic and the Ukraine war, which caused supply to fall below demand; second, pandemic stimulus checks, which caused demand to exceed supply.

According to the mainstream account, the first factor drove up firms’ costs, leading them to raise prices. The second factor enabled firms to raise prices even further. This fed back into further increases in costs for suppliers, and thence to further increases in prices by firms, leading to an inflationary spiral.

Antimonopolists accept that supply chain snarls and stimulus-driven demand increases provided the initial inflationary impetus. But they insist that this alone was not enough to get the spiral going. They argue that all that this did was to create the psychological prerequisites for an inflationary spiral.

At this point, they argue, market concentration stepped in to create the inflation. Specifically, they argue that once consumers had experienced an initial increase in prices due to the pandemic and later the Ukraine war, they became psychologically primed to attribute price increases to forces majeures of this kind. Antimonopolists argue that this created an opportunity for big firms tacitly to collude to raise prices further.

Market concentration matters here because tacit collusion is possible only when the number of players in a market is small. But according to antimonopolists, concentration alone was not sufficient for tacit collusion to take place until consumers were primed by crises to accept higher prices.

Big firms could tacitly collude to raise prices because consumers, believing that price increases were an inevitable result of the global crises, were willing to pay those higher prices. Consumers would not recoil in righteous indignation, punishing firms by buying less, but instead would continue to buy at the higher prices.

In economic terms, consumer willingness to pay increased by more than the extra money they received from stimulus checks justified. That extra demand created an opportunity for firms tacitly to collude to increase prices.

The Inframarginalist Story: Firms Rationed with Price

The antimonopoly account of inflation doesn’t actually withstand scrutiny on its own terms. But I will get to that later.

What’s important to notice now is that the argument is more complex and overdetermined than it needs to be when it comes to making a progressive, moral case against business behavior during this inflation.

Progressives seem to think that they need to tell a story about market concentration, collusion, or monopoly, in order to blame firms for the present inflation.

They don’t.

All the elements they need to make a moral case are right there in the mainstream account. No collusion or monopolization is required.

That’s because when supply chains snarled and demand surged, firms had a choice. They could have responded by rationing their inventories based on a rule of first-come-first-served or some other principle of distributive justice.

Instead, they chose to ration with price.

That is, when supply chains snarled and stimulus checks caused demand to outstrip supply, firms could have kept their prices where they were and just let their goods to sell out. That amounts to rationing based on a rule of first-come-first-served. Instead, they chose to raise prices.

In the short run—which is all that matters when it comes to getting an inflationary spiral started—raising prices doesn’t increase supply. It takes time to ramp up output, especially when ports are clogged or sanctions against Russia foreclose sources of supply.

But raising prices does ration output to those who can afford to pay the highest prices, which usually means the rich. It also has the rather nice attribute, from the perspective of firms, of increasing profits. In the short run, the inventory that firms have on hand has been acquired at low, pre-crisis costs. Every additional dollar that firms charge for that inventory is profit. It is a redistribution of surplus from consumers to firms.

It therefore follows directly from the mainstream economic account of the current inflation that the root cause of the inflation was corporate greed—specifically, the choice of businesses to ration with price instead of based on some other metric.

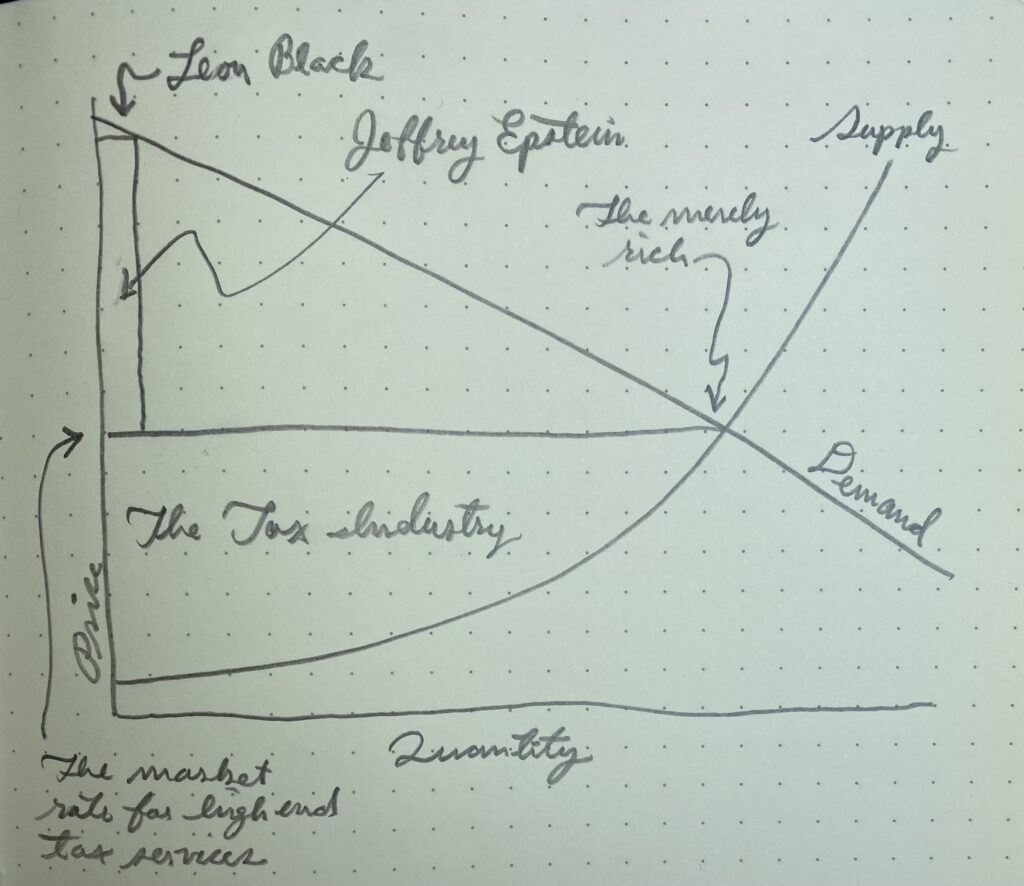

Graphically

In partial equilibrium terms, we have something like this. We start with a competitive market for the firm’s product.

Then there’s a supply disruption or a demand surge that restricts output in relation to demand. Graphically, the supply curve kinks upward rather steeply. The firm then has the option to charge a low price at which the good sells out or to charge a high price that rations access to those with the highest willingness to pay. The high price also generates extra profit.

If the firm chooses the ration price, buyers pass the price increase along through the tangled loop of supply chains that is the economy. Buyers’ ability to pass the increase along effectively increases their willingness to pay for the good, so the demand line rises. The passing-along of the price increase travels through that tangled loop until it increases sellers’ costs, which is reflected in an increase in the supply line. This increase in the supply line reduces firm profits at the current price (the area below the original “greedy, inflationary price” and the higher supply line). The firm moves to restore those profits by increases its price in turn. We are off to the inflationary races thanks to the firm’s initial decision to ration with price instead of letting goods sell out in response to the shortfall of supply relative to demand.

There Is No Efficiency Justification for Rationing with Price

Economists used to argue that rationing with price is necessary, notwithstanding its ugly distributive effects, because it is efficient. Keeping prices low and letting goods sell out forces people to wait on interminable lines, wasting time that could be spent doing more productive things.

As I’ve argued elsewhere, in the information age that’s no longer true. It takes the time required to open up a webpage to reserve a place on line—or to know whether a good has sold out.

Economists also argue that non-price rationing leads to wasteful attempts to subvert the rationing system. People invest in bots, for example, designed to subvert digital lines. But, as I’ve also argued elsewhere, that argument is an example of the Nirvana fallacy. It ignores that people already waste lots of resources attempting to subvert the price system. People expend great effort on wasteful attempts to acquire the money they need in order to be able to pay the prices that firms use to ration access to their products. Theft and corruption are examples.

Indeed, the vast infrastructure of the criminal law and its administration, as it relates to financial crimes, is a monument to the waste associated with operating a price system.

Economists also sometimes argue that rationing with price allocates goods to those who value them the most. But few really believe that. Economists have known for a long time that willingness to pay is a poor proxy for utility because the rich are often willing to pay more than others for things that they value less than others do. As I’ve argued elsewhere, it’s unclear that place in line is a less accurate proxy for value than willingness to pay.

All of which is to say that a firm’s decision to ration with price is not necessarily efficient.

But, as we have seen, it is profitable.

And indeed a firm’s decision to ration with price is inefficient to the extent that it can trigger an inflationary spiral. The reason inflation is inefficient is that it makes it difficult for buyers to plan; prices start to change so fast that they don’t know what their money will buy tomorrow. That shuts down economic activity.

The Greed of Firms Both Small and Large Will Trigger Inflation in Response to Supply or Demand Shocks

It’s important to understand that monopoly or even market concentration is not required to tell a story about greedy price-rationing.

Whether a firm is a monopoly, or a big player in a concentrated market characterized by tacit collusion, or a bit player in a highly competitive market, the firm will have the option to raise price in response to supply or demand shocks—so long as the shocks cause industry demand to exceed industry supply in the short run.

To see why this is true in competitive markets having lots of small sellers, consider what happens when industry supply falls below industry demand.

Some group of buyers won’t be able to find sellers who are willing to sell to them. That’s what it means for demand to exceed supply. We can imagine these buyers going from seller to seller begging for access to goods. Each seller, no matter how large or how small, will face a choice: the seller can either say “sorry, I’ve already promised by stock to someone else.” Or the seller can say “I’ll redirect my stock to you if you pay me a more than the other guy.”

That is, every seller, no matter how big or small, faces the choice whether to ration based on a rule of first-come-first-served (or some other basis apart from price), or to ration with price. When prices rise in competitive markets in response to supply or demand shocks, that’s because each tiny market participant is choosing to ration with price.

Each is choosing to exploit the crisis to make an extra buck.

What is true of competitive markets is true of concentrated markets as well. Supply and demand shocks can drive up the profit maximizing price in the market, but the big firms that have the preexisting power to charge such prices don’t actually have to adjust their prices upward in response. They can continue to charge their legacy, pre-crisis prices.

When they choose instead to raise prices, they are exploiting the crisis to make an extra buck.

The progressive case that corporate greed lies at the heart of the present inflation does not, therefore, require an antimonopoly story. All it requires is the basic recognition that, when firms raise prices in the short run in response to supply or demand shocks, they are engaged in one thing only—exploiting a crisis to redistribute wealth to themselves, and thereby triggering an inflation that could make everyone worse off.

Why This Is an Inframarginalist Story

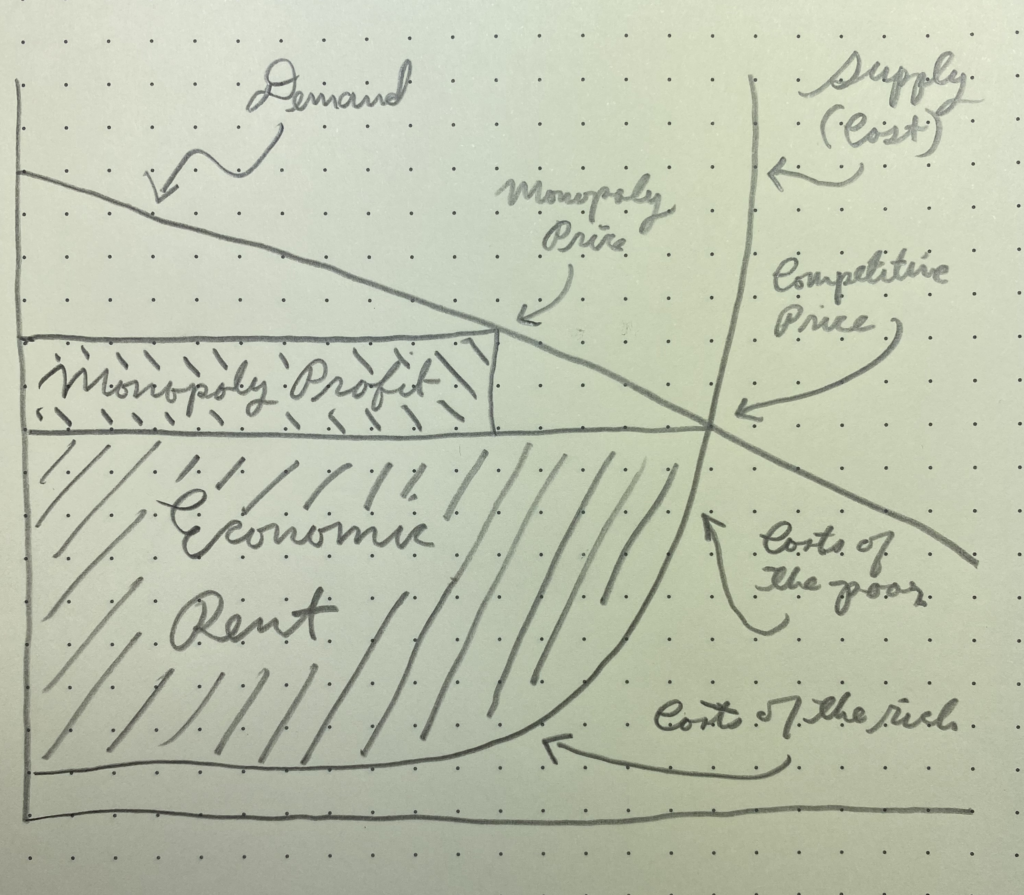

The inframargin is the category of market transactions in which surplus is generated and distributed. In a competitive market, the marginal buyer and seller place the same value on the good and so their exchange generates no surplus.

The greedy price-rationing story is an inframarginalist story because it emerges from a laser focus on the way prices distribute surplus in markets.

When the inframarginalist sees prices rising, the inframarginalist asks whether the price increases are necessary to cover costs. If not, then the price increases are redistributing surplus—and posing the question whether that redistribution is desirable.

It’s thanks to this process of thought that the inframarginalist perceives that short run price increases during a crisis are not driven by costs. Output adjustments, even costly ones, take time, and until they have been undertaken, firms are selling their legacy, low-cost inventory.

It follows that short-run price increases are elective. They are effectively a policy decision on the part of firms to take advantage of a shortage to redistribute surplus to themselves.

Antimonopolists miss all of this because they spend their time looking for market concentration. For them, redistribution is an afterthought—the stylized consequence of monopolization or collusion.

Implications for Inframarginalism in Relation to Antimonopolism

As I suggested above, the inframarginalist story is a better story for progressives to tell than the antimonopoly story because it is simpler and broader. All you need is evidence that demand exceeds supply. You don’t need market concentration and you don’t need claims about the psychology of consumers or the social behavior of firms.

To be sure, the inframarginalist story does require claims regarding the efficiency of price increases during a crisis that are not needed to make the antimonopoly case. But the notion that willingness to pay is not a particularly good proxy for value, or that in the digital age we don’t spend much time waiting on physical lines anymore, are hardly controversial. Claims regarding consumer psychology and firms’ capacity for tacit collusion are.

The inframarginalist story is also a better story because it represents a more fundamental critique of the economic system. It points to a structural flaw in markets as such, rather than to a market imperfection.

The inframarginalist story basically says: in a crisis, prices in every market—perfect or imperfect, competitive or monopolized, concentrated or unconcentrated—are going to rise even though efficiency does not require that they do, so long as firms remain greedy, profit-seeking entities. There’s nothing that can be done to restructure markets in ways that will prevent this from happening. The only solutions are government regulation of price, taxation of profits, or a reorientation of executives’ legal duty of care away from profit maximization.

The antimonopoly story says: during a crisis, prices are going to rise primarily in concentrated markets, and the solution is to deconcentrate them. There’s no problem with markets as such, and, as a result, greed is for the most part good—it leads to competition in markets and ultimately to efficient outcomes. The problem we face today is merely a problem of market imperfection. If we solve it, then government can go away.

Progressives’ current romance with antimonopolism in the inflation context has been particularly painful to watch because it has lately swept in a scholar who really knows better, and caused her to shoot herself in the foot. Isabella Weber made a splash last year arguing that that the Biden Administration should consider price controls as a solution to the present inflation.

But then last winter she released a paper arguing that tacit collusion explains the inflation. Although I suspect that Weber continues to support price controls as an inflation remedy, the implication of her paper is that price controls may not be the solution after all. Instead, an economy-wide campaign of deconcentration might do the trick.

The inframarginalist account of the present inflation provides stronger support for price controls because it applies regardless of the level of concentration in markets.

The Antimonopoly Account Is Also Incoherent

As I suggested above, the antimonopoly story is not just too complex and too narrow, it also does not withstand scrutiny on its own terms.

That’s because consumer desensitization to price increases will drive up prices in all markets, regardless of the level of competition and regardless whether firms in concentrated markets are tacitly colluding or not. Concentration and tacit collusion therefore aren’t actually required for the story that antimonopolists wish to tell.

If consumers become desensitized to price increases, prices will rise in competitive, unconcentrated markets. Imagine a perfectly competitive market consisting of numerous small sellers. If consumers become desensitized to price increases because pandemics and wars suggest to them that increases are inevitable, then firms that once could not sell to consumers in the market, because their costs, and hence the minimum prices they were willing to charge, were too high, will now be able to sell to consumers in the market. Other firms in the market that have lower costs will observe this and will raise their prices to match those of the high-cost firm. For if consumers can now afford to pay that firm’s prices, they can now afford to pay that price to any firm. As a result, the market price will increase.

The analysis does not change for markets that are concentrated but also competitive. The increase in demand will bring a higher-cost competitive fringe in the market, and the higher prices that fringe needs to charge in order to enter the market will enable all firms in the market to increase their prices.

Prices will also rise in concentrated markets in which firms are already engaged in tacit collusion, so long as the increase in demand also increases the profit-maximizing industry price. Perceiving that demand has increased, big firms will collude further to raise their prices. But they won’t do this because the increase in demand facilitates collusion, but rather because they are already colluding to charge the profit-maximizing price and the profit-maximizing price has increased.

It is possible that firms in concentrated markets might find it easier to initiate tacit collusion when consumers expect price increases. If each firm knows that the others expect consumer demand to rise, creating opportunities to increase prices, each firm may be more confident that a price increase will be matched by other firms.

But against a backdrop in which firms would raise prices in both concentrated and unconcentrated markets and whether they have been colluding or not, it is not clear what any additional price increases due to greater ease of collusion contribute to the inflation story. For the story to work, antimonopolists would need to show that price increases absent the additional collusion would have been insufficient to trigger the inflation. This antimonopolists have not begun to do. Without it, consumer desensitization tells an inflation story without the need for concentration or collusion.

Indeed, consumer desensitization to price increases is a demand story and not a concentration story. And as a demand story, it just puts us back at the basic structural fact of this inflation, which is that it was triggered by an excess of demand over supply that firms big and small chose voluntarily to exploit.

Weber and her coauthor seem to have been led to think otherwise by listening to a bunch of earnings calls in which representatives of firms in concentrated markets suggested that they were raising prices because they were confident that competitors would not try to undercut them.

But to the extent that executives can be assumed to understand what they are doing—which is not a foregone conclusion by any means—all this shows is that, when firms engaged in tacit collusion encounter demand increases, they raise prices. It does not establish that they started tacitly colluding for the first time due to the demand increases. And it does not establish that firms in unconcentrated markets encountering the same demand increases are not raising prices as well.

The antimonopoly argument turns out to be based on a snapshot of how big firms in concentrated markets behave. But if you only look at behavior in those markets you are not going to be able to perceive whether their performance is unique to them or not.

* * *

Progressives want to tell a story about greed and inflation. To tell it with the greatest possible generality and power, they should ditch the antimonopoly blinders.