In art, we reserve the word “elegant” for works that hide the difficulty of their execution. The elegant work is at once powerful and simple. Though the author may have spent a lifetime on its composition, there is no hint of effort in the work. Once the scaffolding from which the sculptor worked is removed, once the guidelines of the draftsman have been scrubbed from the page with an eraser, once the manuscript has been retyped and the markup trashed, only simplicity and perfection remain. The work might as well have sprung fully formed from the head of Zeus.

We should also strive for elegance in the provision of goods and services, and that can mean only one thing: free. That is, the experience of acquiring goods and services, which is the characteristic experience of economic activity, should be as simple as walking in and taking. That is the only elegant way to acquire.

Any other approach reveals the superstructure that supports production, and is decidedly inelegant. To ask for payment is to admit that production is hard. You have suffered and so you require compensation. And to be asked to pay exposes you to all of the tradeoffs involved in economic activity. You must decide whether you can afford the good, and this in turn invites you to meditate both on the reasons for which you are poor (that is, the scarce talents or good fortune that you lack) and the reasons for which the good you wish to acquire is so scarce that it commands a price. You are forced to peer for a brief moment into the inner workings of the economy—the gears, and production functions and demand curves—that run together to foist a price on you.

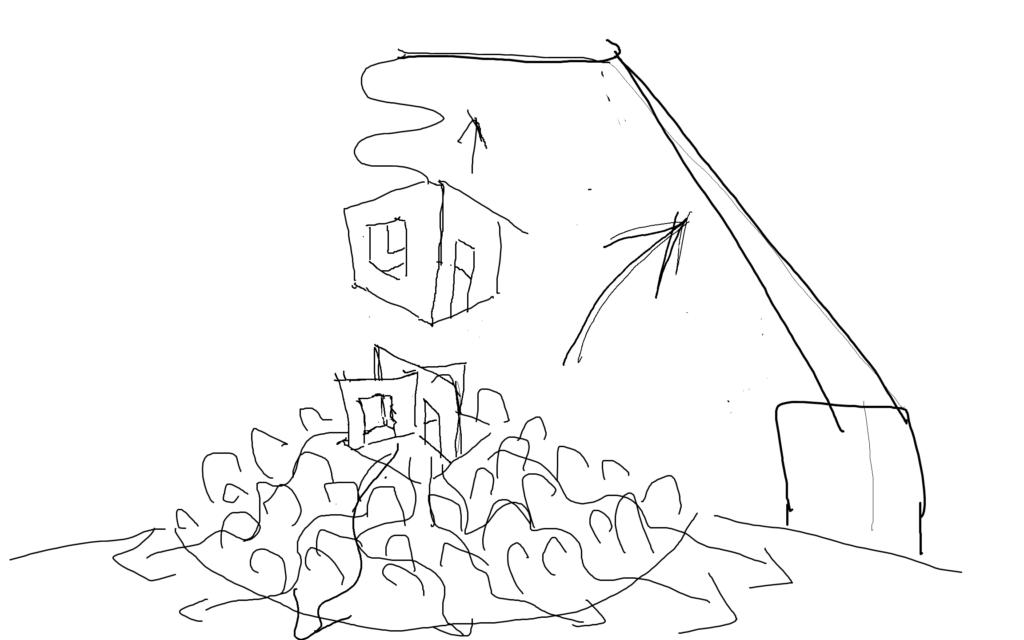

It is rather like being asked to view Michelango’s David with the scaffolding still attached, or the Mona Lisa with the grid lines through which Da Vinci painted still pulled across the lady’s face. Or perhaps even more justly, it is rather like being asked to watch a film by hanging about the set and viewing each monotonous take after another—instead of relaxing in a theater to behold the final cut.

There is nothing so damaging to the enjoyment of a thing than to meditate on what one had to give up in order to obtain it.

The challenge for economics is fashioning a system that at once promotes economic growth and maximizes the opportunity to acquire without worrying about whether one can afford the good.

It follows that an elegant economics should strive not to maximize the responsibility of the individual for economizing—as economists strive to do today—but rather to obscure the problem of economizing from the individual, to hide it so cleverly that people can go through their lives unaware that they are in fact subject to the inevitable laws of scarcity.

Because scarcity is real, nothing can actually be made free. Everything must be produced and so paid for. But there are ways for the clever economic artist to minimize the experience of paying.

The most important is the bundle. To minimize the experience of paying, reduce the number of times in which people actually must pay for things. To minimize the number of times in which people actually must pay for things, sell things together in bundles.

Economics already has a logic of bundles. Today, economists promote bundles when the parts have synergies, so that the whole is more valuable to consumers than the sum of the parts. Consumers prefer the iPhone, with its closed architecture that deprives customers of choice regarding what battery to use or what operating system to install, because when Apple bundles its selection of these things together the phone “just works” at a higher level than more customizable phones.

I mean something different.

Bundles, even when they do not exhibit technical synergies, can be elegant so long as the bundle is not so large that the price speaks loudly of scarcity. Consider the old airline economy class bundle, which included free checked bags, your choice of economy seats (no extra fees for an exit row), a reasonably-sized seat, and a full meal during the flight. After paying a somewhat higher fare, you didn’t need to think of scarcity again until you bought your next plane ticket. Checked baggage, meals, and seat selection bundled together aren’t greater than the sum of their parts—in fact they’re delivered in the same way when sold as a bundle as when you are charged separate bag fees, seat fees, and so on. Bundling them together adds value solely because it obscures scarcity. When they are bundled, passengers are not reminded of the sizes of their pocketbooks when they sit down to pack, when they choose a seat, and when they start feeling hungry mid-flight.

We get a hint of this, too, in the all-you-can eat buffet. Maybe it’s just clever marketing: diners think they get a better value when on average they don’t eat as much as the extra bucks they pay for their meal. Or maybe it has to do with elegance. It’s nice to be able to ask for seconds without worrying about the price.

Which begs the question: if it’s so nice, why don’t firms offer more bundles of this kind? Doesn’t the fact that the trend in recent years has been toward unbundling products and services suggest that consumers actually prefer to be able to choose what they pay for and what they don’t?

That could be. But the logic of elegance also suggests that consumers are never really presented with a choice between the two systems, even when a firm offers the option to pay more for a bundle or less for a la carte service.

Here’s why.

Suppose that an airline offers a full-service ticket that includes priority seating, a full meal, and free checked baggage and also offers a somewhat cheaper ticket that includes just a seat, with the other services provided a la carte. In this case, the cheaper ticket is the elegant solution in that it it speaks less of scarcity than the more expensive ticket. That is, when faced with a choice that involves a lower-price option and a higher-price option, consumers will tend to prefer the lower -priced option, even when it involves less value for money, simply because a lower price speaks less of scarcity than a higher price.

In order to elicit a true comparison of consumer preferences, one would need to place the consumer in a world in which only the lower-priced option is offered and then place the consumer in a world in which only the higher priced bundle is offered, and then ask the consumer to compare his relative pleasure in the two worlds. That can never be done perfectly because the options can never be offered at the same time—although in cases in which there has been a historical change, as with airlines, the recollections of people who lived through both regimes offer some guidance. Ultimately, we must guess which of the two worlds confers more pleasure.

An elegant economics concludes that consumers prefer bundling when it can be had at reasonable cost.

All this is not to say that everything should be bundled so that we end up with something like a centrally planned state in which the government sells you a single bundle called “the luxuries and necessities of life.” The bigger the bundle, the greater the waste, because market signals are reduced. In the years immediately after the discontinuance of economy meals on domestic flights, airport kiosks sold meal trays that mimicked the ones that had once been served on flights. Today, those are rare; indeed, people don’t seem to do much eating of meals at all on domestic flights. That suggests that for years airlines provided a meal perk that customers may not have valued much at all.

There is an optimal bundle size, neither too small nor too big, but if one takes elegance into account, it is likely much greater than what we have today.

But it is worth noting how much apparently elegance-based bundling already exists in the economy. Consider, for example, pleasant customer service. There’s no synergy created with your pizza by a cashier’s smile, and yet businesses encourage their cashiers to smile. They could charge a premium for it—and through tipping cashiers themselves may do something like that—but they don’t. The checkout experience is vastly more elegant when the purchase price covers a smile plus pizza rather than just pizza.

In fact, there are an immense number of freebies of this kind that go into every good or service offered by a business—things that a business thinks consumers would be pleased to see included but for which they likely would not pay if offered a la carte.

We often assume that these things are offered to achieve a competitive advantage, but the successful unbundling of the air transport product, of which the same assumption might easily have been made, suggests otherwise. Businesses themselves have a basic taste for elegance and it often takes a corporate raider or efficiency expert to suppress it. (Yes, the airline industry has consolidated over time, so the unbundling could have had something to do with a decline in competition, but keep in mind that this started twenty years ago.)

Another example is average cost pricing. In certain apartment buildings in certain older American cities, it remains the case that residents receive no utility bills. The cost of utilities—water, gas, and electricity—is averaged across all renters and included in their monthly rent. This is an elegant arrangement for it reduces the number of bills a renter pays, greatly obscuring scarcity. To be sure, some residents—power users—gain relative to a system of individual billing and others—those who use less—lose out. But as few are able to monitor the usage of others, no one knows who the losers and winners are. So long as there is no extreme abuse of the system—a resident taking advantage of average cost electricity pricing to run a crypto mining operation, for example (and a little policing by building management can root any out)—residents can go about their lives as if utilities were free.

The same is true, of course, of government-provided goods and services. The trend in recent years has been for government to try to allocate costs to users. Think about steep visa application fees designed to cover the costs of immigration services. But it is much more elegant to pay for the service out of general tax revenues, so long as abuse can be policed at reasonable cost. Many Americans advocate, for example, for “free college”, as if government provision of education would somehow make it free. They really pay for college through their tax payments, but because they rarely know the precise amount that they contribute toward any particular service, it is rather as if they contributed nothing at all. When people say “free” in this context, they are telling us something important about how elegance works in economics. The less you know about scarcity, the free-er you feel yourself to be.

If the foregoing analysis is right, then the great movement in recent decades in favor of creating markets in everything has ultimately been bad for America, because it has forced consumers to confront scarcity in myriad places in which it had once been hidden. Consumers now must confront scarcity with respect to almost everything they do when they fly. In some cities, they confront it in the form of paid fast lanes when they drive. They confront it in streaming television, where they are increasingly asked to buy a la carte. They confront it in purchasing movie tickets; the good seats are now priced higher. And so on.

Elegance in economics does not only require that paying be concealed but also that other experiences that suggest scarcity be conceal as well.

Consider, for example, the mega-project. Because a mega-project serves a great many people, the cost per person in terms of a toll for use is low. A private business undertaking the project will build a facility that is just large enough to accommodate peak demand.

But to be in an airport that is just large enough to accommodate a crowd is to come face to face with the problem of scarcity. Of space. Of customer service representatives. Of patience.

An elegant economics would require that the builder calculate the minimum space required to meet peak demand—and then double it.

This would certainly be a problem for smaller projects with large per unit costs. For the doubling would drive the toll up a great deal, and being asked to pay a lot for something is just as rudely indicative of scarcity as is occupying a small facility during peak demand. But for a mega project in which per person costs are very low, a doubling will barely register in the mind of the consumer. To pay $2 to enter an airport rather than $1 speaks rather little of scarcity. And the payoff, in terms of the elegance of feeling as though one were alone in a vast space, is great. Imagine that every airport in the country had been built to twice its current size so that no matter how many people were flying on a given day there were always lots and lots of space.

In our inelegant economics of today, this would never be tolerated. A private business would never spend twice what it needs to spend to complete a project. And if it were induced to do that by a government which, for example, offered loans to finance larger projects, the cry would be: “overbuilding.” But overbuilding—within limits—should be our aim for every large project, so as to minimize the experience of scarcity and to maximize the experience of easy plenty.

To understand elegance in economics, we must draw an analogy between economics and architecture. The classical architect engaged to build a wall could choose merely to deliver a blank face to you—and some modern architects would do just that. But the classical chooses instead to add an entablature—a set of lines cut superficially into the stone that run along the top of the wall. Why does he do that?

Because the grooves—or, rather, the shadows that the grooves create—make it easier for the eye to grasp the size and shape of the wall. A blank face has no scale and no form. Groove it in the right way and the eye knows immediately the extent of what it beholds. The purpose of embellishment in architecture is to make it easier to consume the work on a visual—indeed, mental—level. In the same way, the purpose of elegance in the provision of goods and services is to make the process of acquisition easier on a mental level. Both approaches have costs. It is cheaper to build a wall without an entablature, and bundling or socializing services leads to waste.

But elegance is a good, and all goods have costs.