The tendency to ascribe the problem of inequality that ails us to the bigness of firms is the great embarrassment of contemporary American progressivism. The notion that the solution to poverty is cartels for small business and the hammer for big business is so pre-modern, so mercantilist, that one wonders what poverty of intellect could have led American progressives into it.

Indeed, the contemporary progressive’s shame is all the greater because the original American progressives a century ago, whose name the contemporary progressive so freely appropriates, did not make the same mistake. The original progressives were more modern than progressives today, perhaps because the pre-modern age was not quite so distant from them. Robert Hale, the greatest lawyer-economist of the period, wrote that

[e]ven the classical economists realized . . . competition would not keep the price at a level with the cost of all the output, but would result in a price equal to the cost of the marginal portion of the output. Those who produce at lower costs because they own superior [capital] would reap a differential advantage which Ricardo, in his well-known analysis, designated “economic rent.”

Robert L. Hale, Freedom Through Law: Public Control of Private Governing Power 25-26 (1952).

I suspect that this is absolute Greek to the contemporary progressive. I will kindly explain it below.

But first, it should be noted that the American progressive’s failure to appreciate the smallness of the bigness problem is not shared by Piketty, whom American progressives celebrate without actually reading:

Yet pure and perfect competition cannot alter the inequality r > g, which is not the consequence of any market “imperfection.”

Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century 573 (Arthur Goldhammer trans., 2017). (Italics mine.)

What does Piketty mean here?

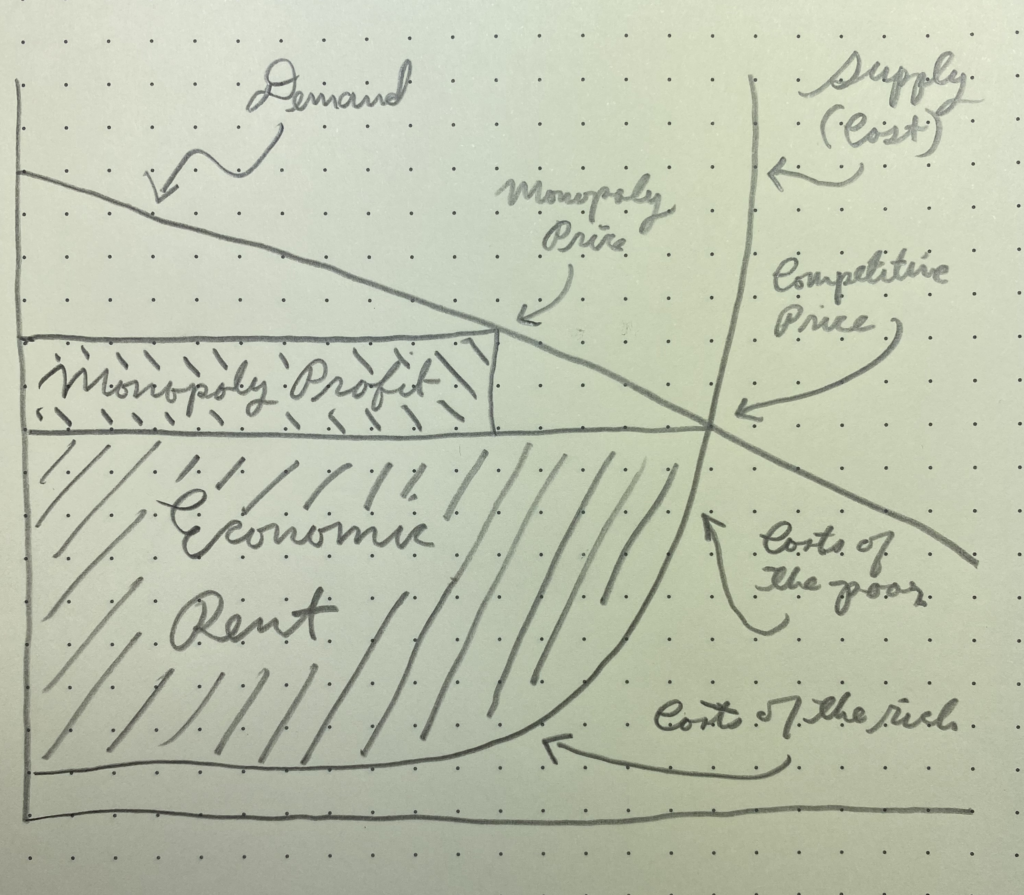

He means what Hale meant, which is that the heart of inequality does not come from monopolists charging supracompetitive prices, however obnoxious we may feel that to be, but rather from the fact that the rich own assets that are more productive than the assets owned by the poor, and so they profit more than the poor even at efficient, competitive prices.

In other words, the rich get richer because their costs are lower and their costs are lower because they own all the best stuff.

No matter how competitive the market, prices will never be driven down to the lower costs faced by the rich, because other people own less-productive assets than do the rich and competition drives prices down to the level of the higher costs associated with producing things with less-productive assets.

(Why can’t price just keep going down, and simply drive the more expensive producers out of the market to the end of dissipating the profits of the less expensive producers? Because there is always a less expensive producer! Price can therefore never dissipate the profits of them all, and anyway demand puts a floor on price: consumers are always bidding prices up until supply satisfies demand.)

Graphically, American progressives have been sweating the “monopoly profit” box without seeming to realize that it’s tiny compared to what remains once you eliminate it, which is the “economic rent” box.

Picketty, the original American progressives, and kindergartners know the difference between big and small. Why don’t we?

One reply on “The Smallness of the Bigness Problem”

[…] The Smallness of the Bigness Problem (Ramsi Woodcock – What Am I Missing?) […]