All courts do all day in civil cases in which the remedy is money damages is to engage in personalized pricing in favor of consumers. The plaintiff is the producer, the defendant is the consumer. And the damages amount is the price charged to the defendant for whatever it is that the defendant has taken from the plaintiff in violation of law, whether dignity, reputation, an arm or a leg.

When private enterprise personalizes prices, it chooses the highest possible prices: price equal to the maximum that the consumer is willing to pay. That is, firms strive to engage in perfect price discrimination.

Courts do the opposite. They personalize the prices of legal wrongs to be the lowest possible prices consistent with compensating victims: price equal to the cost to the plaintiff of the violation of law, and not a penny more. That is, courts strive to engage in what I have called perfect cost discrimination.

That’s weird, when you think about it.

All lawbreaking amounts to a forced sale. The defendant who shoots off the plaintiff’s arm forces the plaintiff to sell his arm to the defendant, or at least to sell the defendant the service of having an arm shot off, and whatever attendant satisfaction that provides the defendant, whether in the form of a feeling of security, the pleasures of power and domination, revenge, or what have you.

The law, in prohibiting battery, recognizes in the plaintiff a right to payment for the service. And if the transaction were not forced, and the plaintiff were to have any amount of market power, which we would expect to exist in spades with respect to the subject of many prohibitions–very few people are willing voluntarily to part with their arms, for example–then the plaintiff would almost surely charge a price for the arm above the bare minimum necessary to compensate the plaintiff for the harm. That is, if the exchange were voluntary, the price would in many cases be much in excess of cost, and indeed much closer to the maximum that the defendant would be willing to pay. Indeed, it seems reasonable to suppose that the defendant forces the transaction precisely because the defendant hopes to avoid being charged a price equal to the maximum the defendant is willing to pay.

So you would expect the law to provide the plaintiff with something closer to the bargain that the plaintiff would have struck voluntarily with the defendant. That at least would ensure that the defendant enjoys no gain from breaking the law and forcing a transaction.

But the law doesn’t see it that way.

The “rightful position” principle in remedies teaches that courts should measure damages in order to put the plaintiff in the position that the plaintiff would have occupied if the defendant had not engaged in the bad act. That causes courts to set the lowest possible price for breaking the law, rather than a price that approximates the voluntary price. For the position that the plaintiff would have occupied without the bad act is assumed to be the one in which no transaction takes place at all and the harm of the transaction has therefore not been inflicted. So damages under this measure just equal the amount necessary to compensate for harm. That is, the cost of the transaction to the plaintiff.

Law and economics scholars have made much of this cost-based baseline, arguing that it leads to optimal deterrence. The idea is that it forces the bad actor to internalize the costs of his actions. And so he will only act to break the law if the gains to him exceed the costs, which is to say, only if cost-benefit analysis shows that the action is efficient.

But that ignores something rather important about optimally-deterrent pricing: there isn’t just one optimal price. So long as the price the defendant pays for the forced sale is personalized, which it must be in a legal system in which judges award damages on a case-by-case basis, any price between cost and the maximum the defendant is willing to pay for the harm is optimally deterring.

Only a price above the maximum that the defendant is willing to pay–as opposed to cost–prevents the defendant from forcing the sale when the benefit exceeds the cost. So only such an extraordinarily high price is non-optimal. The maximum the defendant would be willing to pay is a measure of the benefit to the defendant. So only a price above that maximum drives the defendant away. There isn’t one optimally deterring price, but a range, that from cost all the way up to the maximum the defendant is willing to pay.

Where the courts set the price of illicit conduct within that range matters, because price determines the distribution of wealth between the plaintiff and the defendant, the victim and the injurer. By setting the price equal to cost, courts today achieve the perverse outcome of allowing the injurer to retain all of the gains associated with the forced transaction.

To fully appreciate this perversion, imagine that you decide voluntarily to sell your house. You could sell it at cost, including a reasonable return on investment. But that would be disappointing. What you’d like to do is sell it at the highest price anyone is willing to pay for it. If you do, then you extract all of the value created by the transfer. The buyer obviously places a higher value on the house than you do, otherwise he wouldn’t buy and you wouldn’t sell, and because you charge the highest price the buyer is willing to pay, you cause the buyer to pay out all of that excess value over to you.

By contrast, if you sell at a price equal to cost, including a reasonable return on investment, you don’t extract any of the excess value buyers place on the house. What you paid plus a reasonable return is the value you place on the house, the reasonableness of the return being enough to make you sell at that price. So when you sell at that price, the buyer pays you your valuation, and not a penny more.

Selling at a price equal to cost, including a reasonable return on investment, doesn’t therefore enrich you at all. It just lets you break even in a sense: you give up your house in exchange for a price equal to the value you place on the house.

But now suppose that you decide not to sell the house. You don’t like the price the buyer is offering. You believe the buyer is willing to pay more and you want to hold out until he does. And the buyer responds by bursting in your door one morning, holding a gun to your head, and telling you to clear out permanently, which of course you do, before filing a lawsuit. Now the buyer has forced a sale, and the law of trespass allows the court to dictate to the buyer the price that he must pay for your house.

Under current rules on the measurement of damages, the court would award you cost plus a reasonable return on investment, and not a penny more! The buyer could walk away with all of the gains from trade.

(Let’s put aside the fact that almost any court would issue an injunction here allowing you to repossess your house. Perhaps you’re emotionally scarred and don’t want to live there anymore, so all you demand is money damages. And let’s suppose also that your lawyer commits malpractice and fails to request punitives or damages for emotional distress.)

Which means that current damages rules turn over the entirety of the surplus generated by a violation of law to the wrongdoer! They embody the policy that the wealth generated by illegal transactions should be allocated to the scofflaw.

Which, again, is weird.

Now, you might object that courts award damages equal only to costs because the maximum that the wrongdoer would be willing to pay for the privilege of breaking the law is a thing difficult to calculate.

But so too are costs.

For costs are themselves maxima that someone would be willing to pay. The cost of an injury is the maximum that the victim would be willing to pay to avoid the injury. The cost of your house is what you paid for it plus a reasonable return on investment only because that is the maximum that you would be willing to pay to avoid having it destroyed or taken from you. More than that and you could buy a better house. And there is a subjectively element in that cost calculation: the reasonableness of the return is subjective. Current rules in theory should force courts to take that subjective element into account in awarding you compensation for harm equal to cost. And if courts can do that, they should be able to answer the question what the maximum that the wrongdoer would be willing to pay might be, including any subjective element thereof. (Indeed, courts should already do this in restitution cases, of which more below.)

You might also object that the maximum that the wrongdoer would be willing to pay is always less than the cost to the victim, because otherwise the wrongdoer would just be able to enter into a voluntary transaction with the victim to inflict the harm.

But I don’t think that’s right, at least if we want to maintain the fiction of rational decisionmaking that is all of the fun of law and economics and which itself underpins the whole theory of optimal deterrence I wish to complicate here.

The wrongdoer knows that undertaking the bad act will result in liability, and so when the wrongdoer acts, he does so knowing that he will pay a price. If the price is too high, which it will be if he inflicts a harm for which he would not be willing to pay, then he will not act. The courts therefore never can extract damages from wrongdoers in amounts above those which wrongdoers are willing to pay. If they do, wrongdoers simply will not act.

The economic problem for the courts is precisely to find the price that is high enough to ensure that the wrongdoer will not act unless he values the harm more than the victim, but not so high as to prevent the wrongdoer from acting when he does value the harm more than the victim. The trouble is that under current damages rules the courts always choose the lowest possible price.

Now, I don’t mean to suggest that the law is entirely deaf to the problem of gains from trade. One can almost always bring an unjust enrichment action and obtain the remedy of restitution, which does provide the plaintiff with the gains from trade.

But here’s the thing: restitution is an alternative remedy. Either you get restitution, or you get damages, but you don’t get both.

So a plaintiff can receive compensation for the costs to the plaintiff of illegal activity, or the gains enjoyed by the defendant, but not both. Whether the plaintiff opts for one or the other, therefore, the plaintiff will never receive a price for what he gives up equal to the maximum that the defendant is willing to pay, because the maximum that the defendant is willing to pay must equal both the cost to the plaintiff–the value the plaintiff placed on the harm–and the gains to the defendant of inflicting the harm, the excess over plaintiff’s valuation that makes the rational defendant willing to break the law in the first place.

Do punitive damages pick up the slack? It’s true that the pleasure a wrongdoer derives from inflicting harm is in itself probably sufficient to convert an intentional tort into one of malice, and that in turn can lead to punitive damages. But the doctrine of punitive damages suffers from terrible incoherence; we know that it is meant to punish, but does that mean to take some of the ill-gotten gains, or all of them, or to take more than those gains? Unless we are very lucky, punitive damages will either leave some gains with the wrongdoer or charge the wrongdoer a price in excess of willingness to pay, preventing the wrongdoer from engaging in efficient conduct.

Only a reconceptualization of the “rightful position” principle to require that courts measure damages by the maximum the defendant is willing to pay, rather than the cost to the plaintiff, would ensure that defendants do not enjoy gains from the illicit trade that is every offense under the law.

In closing, a word on the relevance of personalized pricing. Why does it matter here that, in engaging in case by case adjudication, judges effectively personalize the price of offenses?

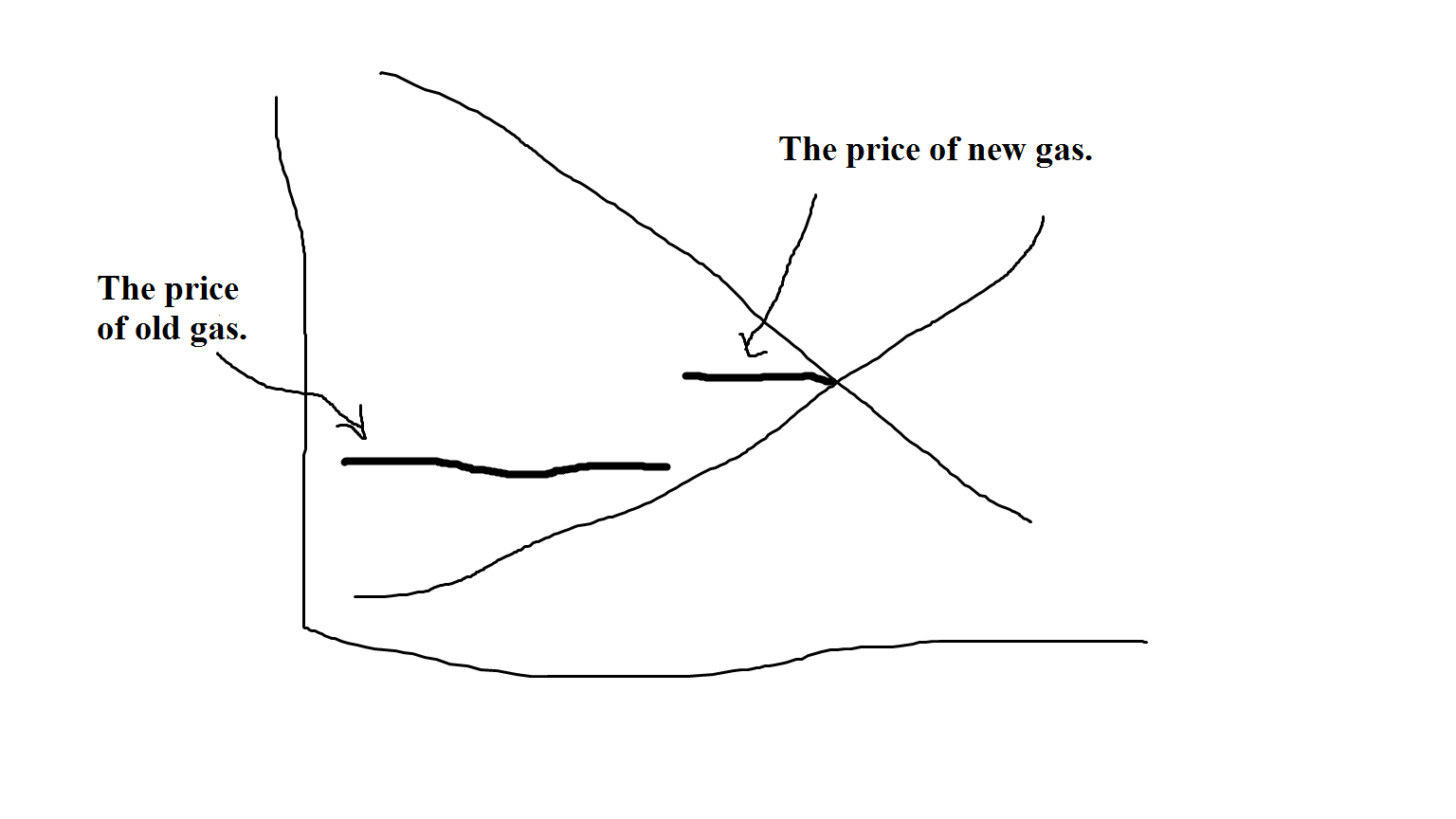

It matters because personalized pricing is efficient whether the price charged is equal to cost or to the maximum the buyer is willing to pay. When prices can’t be personalized, and price is therefore one-size-fits-all for an entire market of buyers and sellers, then there is likely only one price that does not price some buyers or sellers willing to engage in mutually beneficial trades out of the market. That’s the price equal to marginal cost, the competitive price. And that price distributes the gains from trade between all buyers and sellers in the market in a single unique way. Try to change that distribution, by raising or lowering the price, and efficiency suffers: some buyers or sellers will be priced out of the market.

With personalized pricing, however, the court can vary the price charged to one buyer-seller pair–the defendant and plaintiff before the court–without changing the price charged to other pairs, so regardless the price the court chooses in one case, buyers and sellers won’t be priced out of the market in other cases. So the case-by-case character of adjudication opens up a world of distributive options with respect to the market for illegal activity that would not exist if the courts were to engage in one-size-fits-all damages calculations.

It’s a world that the law has failed so far fully to recognize and exploit.