[T]he prosperity of [the town] M. sur M. vanished with [its mayor and leading business owner] M. Madeleine; . . . lacking him, there actually was a soul lacking. After this fall, there took place at M. sur M. that egotistical division of great existences which have fallen, that fatal dismemberment of flourishing things which is accomplished every day, obscurely, in the human community, and which history has noted only once, because it occurred after the death of Alexander. Lieutenants are crowned kings; superintendents improvise manufacturers out of themselves. Envious rivalries arose. M. Madeleine’s vast workshops were shut; his buildings fell to ruin, his workmen were scattered. Some of them quitted the country, others abandoned the trade. Thenceforth, everything was done on a small scale, instead of on a grand scale; for lucre instead of the general good. There was no longer a centre; everywhere there was competition and animosity. M. Madeleine had reigned over all and directed all. No sooner had he fallen, than each pulled things to himself; the spirit of combat succeeded to the spirit of organization, bitterness to cordiality, hatred of one another to the benevolence of the founder towards all; the threads which M. Madeleine had set were tangled and broken, the methods were adulterated, the products were debased, confidence was killed; the market diminished, for lack of orders; salaries were reduced, the workshops stood still, bankruptcy arrived. And then there was nothing more for the poor. All had vanished.

Les Miserables

Category: Antitrust

Amazon paradoxes are proliferating. Here’s another: to the extent that Amazon is engaged in anticompetitive conduct, it is the conduct of opening its website to third-party sellers, not, as Amazon critics hold, the conduct of failing to be even more welcoming to those third-party sellers.

As the Times’ David Streitfeld, who has perhaps done more than anyone else to advance the notion that Amazon is unreasonably severe with third-party sellers, seems slowly to be realizing, Amazon’s third-party sellers are, well, a problem. They sell junk. They sell defective products. They fool their customers. And then they disappear.

As the Wall Street Journal alerted us more than two years ago now: Amazon’s open door policy with respect to third-party sellers, which sellers constitute more than 50% of sales on Amazon.com, has caused Amazon effectively to “cede control of its site,” badly degrading the shopping experience.

Which begs the question: why? Why would Amazon let this happen? The answers is: “dreams of monopoly.”

Every other retailer in the world seems to understand that one of the biggest pieces of value retail can deliver to consumers is: curation. The retailer does the hard work of sifting through the junk and the fakes and the defectives to find the good stuff, so that consumers don’t have to do that themselves. Why do you shop at Trader Joe’s instead of your local supermarket? Because you know that if Trader Joe’s is selling it, it’s probably not only of reasonable quality, but likely tastes great too. That’s the value of curation.

But, as Streitfeld correctly notes, Amazon has all but given up on it. Anyone can list products on Amazon. And the company makes almost no effort to flag the best products for you. Ever since that Journal article, the public has known that “Amazon’s Choice” is just an empty label slapped on a piece of third-party seller junk by an algorithm parsing sales trends. No one at Amazon can vouch for the underlying product’s quality, usefulness, or safety.

You might have hoped, as I once did, that at least the products Amazon itself sells under its own brand names, like Amazon Basics, are competently curated. But those, too, have turned out to be no more than the outputs of sloppy and stupid algorithms. The programs troll Amazon’s site for popular third-party products and flag them to Amazon product teams, which then contact the original equipment manufacturer in China, slap on an Amazon Basics logo, and bring the rebranded product back to market. The result is that the Amazon-branded products can blow up in your face, just like the stuff sold by third-party sellers.

What would cause Amazon intentionally to forego delivering curation value to its customers and so risk alienating them from its website? The answer must be that Amazon gets something that it thinks is even more valuable in return for running this risk.

That thing is scale.

By opening its doors to third-party sellers, Amazon was able to bring much of the commercial internet onto its website, ensuring that if a consumer wanted to find something, he didn’t need to search the Internet, he just needed to search Amazon.com. And that in turn ensured that most consumers would do their online shopping on Amazon. And that in turn ensured that if you wanted to sell something online, you wanted to do it as a third-party seller on Amazon. And so on. In econ speak, opening the door to third-party sellers created massive “network effects” for Amazon, effects that make Amazon.com essential for both buyers and sellers.

Curation would destroy that because curation is costly. Algorithms aren’t good enough to curate effectively, as the piles of fakes, defectives, and junk on Amazon.com today shows. So if Amazon were to take curation seriously the company would need to pay people to do it. And even Amazon can only afford so many people. So Amazon would only be able to curate so many products. Which means that Amazon would not be able to offer everything on its website anymore. Which would mean that everyone would no longer shop on Amazon. Which would mean that fewer third parties would need to list their products on Amazon. And so on. Amazon would be better. But it would also be smaller.

And Amazon would face more competition, because now Amazon’s advantage wouldn’t be its network—the fact that Amazon carries everything and so everyone shops there—but rather the quality of its curation. There can only be one retailer that carries everything and at which everyone shops. But there are lots of retailers that curate—and compete on curation.

So, Amazon’s open-door policy toward third-party sellers, and the danger and frustration to which that exposes its customers, is anticompetitive. At least in the sense that it is meant to extract Amazon from the fierce competition based on curation that confronts most retailers, and to put Amazon instead in the unique position of being flea market to the Internet.

Amazon clearly believes that the benefits it gets from avoiding having to compete on curation outweigh the costs to the company of forcing its customers to wade through oceans of junky, fake, or defective products on its website. How could Amazon not, when imposing those costs on consumers makes Amazon indispensable, and hence immune to any consequences associated with alienating those consumers?

Well, not completely immune. There are still other retailers out there. And the more toxic Amazon’s site becomes—the more it really does come to resemble a flea market—the more willing consumers will be to put up with the cost and inconvenience of shopping elsewhere. I personally no longer buy books from Amazon because I hate dodging fakes on its site—buying elsewhere costs more, and sometimes I have to wait weeks longer for my books to arrive. But I’m happier.

The key for Amazon is finding a way to engage in just enough curation to prevent consumers from leaving in droves, but not so much that sellers abandon the platform and it ceases to become indispensable to consumers.

The irony here is that the anti-Amazon zealots, in fighting, under the banner of “self-preferencing,” every attempt by Amazon to impose order on third-party sellers or to curate by promoting its own brands, are effectively pushing Amazon to retain its monopoly position by continuing to welcome the entire commercial Internet onto its website.

Amazon critics: If you really want to make Amazon small, and quickly, help Amazon to engage in more self-preferencing. Ask Amazon to sell only its own branded products on the site, kicking all third-party sellers off. Or ask it to discriminate more heavily against some third-party sellers in favor of others, until Amazon.com becomes like every other retailer: offering a relatively small selection of products that Amazon believes consumers will like the most.

It should be clear that Amazon’s policy of being a flea market, instead of a normal, curating, retailer, is anticompetitive. But just because something is anticompetitive—in the sense that it harms competitors and hence competition—doesn’t make it bad, or an antitrust violation, unless the conduct also harms consumers. So, does it?

The answer must be no. Because, as I have said, Amazon is not completely immune to consumer dissatisfaction. You can find almost everything sold on Amazon elsewhere; it just takes more time and expense to get it. So Amazon today presents the following choice to consumers, who can shop elsewhere: Speed or safety; A low price or the genuine article; One stop shopping or purchases free from defects. And consumers so far have chosen the former, which suggests that they prefer it.

Antitrust cannot eliminate the tradeoff that seems to exist here between scale and quality. But consumers can decide which they prefer. If Amazon doesn’t do something about its site, if it doesn’t strike a better balance between scale and quality, if the junk and the fakes and the defectives continue, consumers will rebel. They will learn that the extra time and expense required to secure curation is worth it. And Amazon will go down; or change to save itself.

I for one don’t plan on buying any more books from Amazon anytime soon.

By the end of last year, 150 million Chinese were using 5G mobile phones with average speeds of 300 megabits a second, while only six million Americans had access to 5G with speeds of 60 megabits a second. America’s 5G service providers have put more focus on advertising their capabilities than on building infrastructure.

Graham Allison and Eric Schmidt, Opinion: China Will Soon Lead the U.S. in Tech, Wall St. J. (Dec. 7, 2021), https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-will-soon-lead-the-us-in-tech-global-leader-semiconductors-5g-wireless-green-energy-11638915759.

Of course, it’s a bit rich to be reading this in the opinion pages of the Journal, which can usually be found defending laissez-faire commercialism.

The American telecom industry is a marketing-driven oligopoly that colludes tacitly to minimize expensive investment in infrastructure and competes instead for market share via worthless, unproductive advertising.

Things would have been different if we had not broken up the old Ma Bell, an engineering-focused organization that took national defense very seriously. As a monopoly, it knew that it had to serve a public purpose or the pitchforks would come out.

Unfortunately, they came out anyway, and antitrust got it, and we are left with the miserable, middling shards that we have today—shards that quickly replaced their engineering culture with a marketing culture, because once they were small they didn’t need to worry about public scrutiny and were free to work exclusively for themselves.

When you first enter antitrust from the left, you are struck by what appears to be a travesty: that a firm that monopolizes an input can get away with denying that input to downstream competitors.

One thinks to oneself: A monopoly using its power to smash a competitor. How is that not an antitrust violation? An antitrust that fails to prohibit that is a perverse, hollowed-out thing captured by the evil it was constituted to destroy. It is the equivalent of the criminal law not prohibiting killing with malice aforethought. Or the contract law not enforcing promises.

And then you get over it, because actually prohibiting monopolists from denying essential inputs to their competitors makes no sense. (I will explain momentarily.)

The trouble with antitrust today is that those setting the agenda from the left haven’t been in the field long enough to get over it.

And so we are left with the embarrassing legislation against “self-preferencing” that is currently making its way through Congress.

Self-preferencing as a concept is nothing new. It is denial of an essential input to a competitor, something that antitrust has, at various times, called a “refusal to deal,” “denial of an essential facility”, and “monopoly leveraging.”

The tech giant that “self-preferences” owns an essential input—its platform—that it denies to firms that compete with it in selling things on the platform. When Amazon uses its control over its website to prioritize advertisements for Amazon-branded products over those of third-party sellers, it denies full access to the platform input to those third-party-seller competitors.

The reason you cannot ban all denials of access to essential inputs—can’t ban self-preferencing—is that every single product produced and sold in the United States is a vast agglomeration of denials of access to essential inputs, as I point out in a recent paper. To ban all denials of essential inputs is, therefore, to ban production. Full stop.

And so the proposed legislation, which would ban self-preferencing by all firms that have websites with more than 50 million users and a market capitalization in excess of $600 billion, would simply make it illegal to have more than 50 million users and a market capitalization in excess of $600 billion.

The Make or Buy or Market Decision and Input Denial

To understand why all products are agglomerations of denials of essential inputs, it is useful to reflect that a company can go about adding a component to a product in only three possible ways.

The firm can make the product itself. The firm can buy the product. And the firm can let consumers buy the component on their own and attach it themselves. I call this the firm’s “make or buy or market” decision.

The first two options—to make or to buy—are what we conventionally mean when we say that a particular component has been incorporated into a product, and the decision whether to “make or buy” has long been a famous one in law and economics.

What has not been properly understood about these two options is that both always involve the denial of an essential input to competitors. Only the market option is consistent with an antitrust that would prohibit input denial as a blanket matter.

It follows immediately that production—the process of making or buying components and adding them together to generate a product—is impossible without input denial, and that a blanket antitrust ban on input denial would make production impossible.

Consider, for example, the act of adding an eraser tip component to a pencil.

The pencil maker can add this component in three basic ways. First, the pencil maker can manufacture the eraser itself from its basic components. It can buy the chemicals needed to make the eraser dough and then bake the dough in molds to produce the erasers. Of course, the firm would then need to solve the problem of how to acquire the precursors (and the oven, molds, and labor services required to run the operation), so making is in the end always buying. But for purposes of showing that making or buying both involve input denial, that doesn’t matter.

The second way the pencil company can add eraser tips to its pencils would be for it to buy them from an eraser supplier. The company would go out into the eraser tip supply market, find the supplier that offers the best quality at the lowest price, and do a deal.

The third and final way the pencil company can add eraser tips to its pencils—or, better put, can ensure that eraser tips are added to its pencils—would be for the company simply to sell eraser tips to consumers and leave it to consumers to affix them to pencils. The firm might sell eraser-less pencils and also separate eraser caps that consumers can buy and affix to the pencils. Or the firm might put a special ferrule on each of its pencils, perhaps like the one currently included with Palomino Blackwings, that would allow consumers to snap in a properly-shaped eraser that they could purchase separately from the pencil company.

Now, when a firm makes its own eraser tips to place on its pencils, the firm denies access to an input—its pencils—to outside manufacturers of eraser tips who would like their own eraser tips to be included on the firm’s pencils. The firm is in effect competing against those other eraser manufacturers in the market to supply eraser tips for the firm’s pencils, and in choosing to make its own eraser tips, the firm uses its control over pencils—an essential input from the perspective of eraser tip makers who have no way to get their products into the hands of consumers other than attached to pencils—to favor its own homemade product in the eraser tip market relative to those of competitors.

In the language of platforms and self-preferencing, the firm’s pencils are the platform that eraser tip manufacturers need in order to reach consumers, and in choosing to use only its own homemade eraser tips on its pencils, the firm engages in self-preferencing in the eraser tip market.

This is equally true when a firm chooses to buy rather than to make.

When the firm chooses a particular third-party supplier of eraser tips, the firm denies the pencil input to all of the other eraser-tip makers in the market. Once the firm has placed its order, none of the others can reach consumers, at least until the firm places a new order for more eraser tips.

Is Buying Really Input Denial?

There seem at first to be two problems with this argument that buying components is input denial. The first is that the third party supplier whose erasers are not picked by the pencil company at least had a chance to have them picked when the pencil company was still deciding which supplier to use. The supplier presumably lost out in some potentially competitive bidding process, which cannot necessarily be said for the case in which the firm chooses to make erasers in-house.

Be that as it may, it has nothing to do with the basic concept of input denial. A firm is no less forced from a market by denial of an essential input when the input holder thought it would not be profitable to supply the input than when the input holder thought that it would be profitable to supply the input. Indeed, one would expect that the underlying motive for input denial would always be the determination that supplying the input would be less profitable than denying it.

Where Is the Downstream Competition When You Refuse to Buy?

The second problem is that the pencil company does not seem to be competing against the eraser suppliers at all. Unlike in the first case, the pencil company does not actually manufacture any erasers of its own, much less sell them. But if the pencil company is no longer competing with eraser suppliers—just buying from them—then the pencil company cannot be said to be denying essential inputs to competitors.

But that is to miss what really bothers us about input denial. What we dislike about it is not that a product that is manufactured in-house by the denier benefits from the denial, but rather that competitors are harmed and the denier somehow benefits from that harm.

And here we can be sure that the denier does benefit.

For the denier would not choose a particular third-party supplier over others unless the denier stood to benefit from buying from that supplier rather than others. This benefit might come in the form of a discount on the price of erasers. Or it might come in the form of willingness of the supplier more faithfully to execute the instructions of the pencil company with respect to the specifications of the erasers. It might even involve a profit-sharing agreement without the pencil company formally owning the operations of the third-party supplier.

Whatever it may be, the pencil company benefits, and as a result of that benefit it is possible to say that, through the third-party supplier chosen by the pencil company the pencil company does in fact compete in the eraser market, and indeed favors its avatar at the expense of competing eraser suppliers.

In the language of platforms and self preferencing, the firm’s pencils are again the platform, and in choosing to buy from one supplier only—a supplier that necessarily offers some special benefit to the firm otherwise the firm would not buy from it—the platform self-preferences, in the sense that it puts the interests of a favored supplier above those of competitors.

Thus the only two ways in which a firm can incorporate a component into a product—making the component itself or buying the component—are both instances of input denial.

Only Selling Components Directly to Consumers Avoids Input Denial

Only the third means of adding a component to a product—that of selling the component directly to consumers and allowing them to add the component on themselves—manages not to be input denial. Indeed, only this “market” case corresponds to what we mean when we speak of the sort of freely competitive market that antitrust is meant to promote.

Only when the pencil company chooses neither to make the component itself nor purchase it and incorporate it into the pencil, but instead merely makes its pencils available for any consumer to use to affix erasers, does the pencil company make its input—its pencils—freely available for any and all eraser manufacturers to use as a vehicle for delivering their erasers to consumers. For now the question which eraser manufacturer’s erasers should appear on the pencil company’s pencils is no longer answered by the pencil company at all. It is answered only by downstream consumers, who have complete freedom to decide which erasers win out in the eraser market.

That is precisely the world antitrust seeks to create: a world in which firms that control inputs do not decide who wins in the market but rather consumers themselves decide.

But Selling Directly to Consumers Is Not Production

The trouble is: that is not a world that is consistent with the production of products that incorporate multiple components. And because all products incorporate an infinite number of components—it all depends on how you define component; if each molecule is a component of a pencil, then how many components does a pencil have?—it is therefore not consistent with the production of anything at all.

It is a world in which everything is pulled apart and atomized, and the atoms are presented to consumers in a vast menu from which no sane consumer would ever be able to choose because choice would require infinite knowledge regarding how to assemble every single product that we have today from individual atoms on up.

What those setting the antitrust agenda today miss is that banning self-preferencing by, for example, Amazon, does not merely prevent Amazon from favoring its own Amazon-branded products over those of third parties.

It also prevents Amazon from choosing the look and feel of its own website, for Amazon.com is a platform upon which web designers notionally compete in selling web design services for Amazon, and when Amazon designs its own website in-house it necessarily denies access to that input to competitors.

A rule against self-preferencing would require that Amazon enable Amazon users to buy Amazon site design from third party software developers and apply it to the Amazon website, so that every Amazon customer could, in theory, choose his preferred look and feel for the Amazon website.

It doesn’t stop there.

Amazon would also be required to allow customers to choose each and every employee who works at the company, for each of these employees is, in a sense, a labor component of Amazon, and in making hiring decisions on its own, Amazon necessarily prevents other competing workers from using the Amazon platform to supply their labor services to Amazon’s customers.

If this seems absurd, that is because it is.

The market approach to adding components cannot work as a blanket matter, and so antitrust, which is tasked with insisting upon the market approach, cannot be applied in blanket fashion to everything, or even just to everything that has more than 50 million users and $600 billion in assets. It can work only if applied sparingly, severing a component of one product here, a component of another product there, when doing so is thought to be in the best interests of consumers, whose preferences are the ultimate measure of the value of production.

That is why the actual rule antitrust applies, the rule of reason, can be summarized as the rule that input denial is illegal when it fails to improve the product that is ultimately sold to consumers.

Self-preferencing is not, in other words, something that can become the subject of a right, as in: “consumers have a right against self preferencing.” It is instead fundamentally about the best way to organize production in individual markets. The question it poses is whether the input denier can be relied upon to choose the component supplier that will make the product as good as possible for consumers, or whether consumers can instead be relied upon to make that decision.

Because consumers do not want to have to decide how everything they purchase is made, it follows that in almost every case the best answer is to let the input denier make that decision—by denying its input to downstream competitors that the denier believes will do a poor job.

Is Every Input Really Essential?

One might object that while every make-or-buy decision might well involve input denial, it does not involve denial of an essential input—it is not denial of an input by a monopolist of that input, not self-preferencing by a platform monopolist as opposed to any old platform—and so is not the sort of behavior that outrages the antitrust neophyte’s intuition that antitrust should ban input denial.

The pencil company’s effective denial of its pencil to third party eraser tip makers when the company makes its own erasers in-house is not input denial, the argument would go, unless there is only one manufacturer of pencils in the pencil market. Only then would eraser tip makers have no way of getting their wares to consumers other than through the medium of supplying eraser tips to that particular pencil company.

This argument would be good enough were all pencil companies to make the exact same pencil—same size, same wood, same graphite, same barrel color, same name, and so on. Only then would it be a matter of complete indifference to eraser tip makers whether they were to supply tips to our pencil company or another.

But, in fact, save for a few standardized commodities, like Class C crude oil, every company’s product is different from every other, even if only in brand name. The result is that every firm will prefer some inputs to others—find some more profitable to use relative to others—and so input denial will always deprive a firm of something that it cannot get anywhere else. In that sense, all input denials deny essential inputs and every maker of an input monopolizes that input.

Dixon Ticonderoga pencils are different from Palomino Blackwings are different from Faber-Castells, and so putting Acme Eraser Tips on each produces a slightly different finished eraser-tipped pencil, one that may be more or less desirable to consumers and indeed more or less profitable for Acme Eraser Tips. If Acme’s preferred pencil company—let’s say it’s Dixon—stops sourcing from Acme, Acme will end up worse off, even if Acme is able to supply Palomino or Faber-Castell instead. In this sense, Dixon is essential to Acme.

Of course, if there were only Dixon, then the consequences of rejection for Acme would be more severe—not just a hit to the bottom line but perhaps bankruptcy—but is it the magnitude of the harm that bothers us about input denial, or is it that a particular business opportunity has been put off limits?

Product differentiation makes of every input, in other words, a mini monopoly. In the “market definition” analysis that antitrust undertakes in merger and monopolization cases, antitrust has traditionally dealt with this by defining a company as a monopoly only if its products are very different from others’—in the lingo, only if they are not “close substitutes”—choosing an arbitrary cutoff between “too different” and “not different enough”.

But here’s the interesting thing: antitrust does not take this approach in deciding whether an input is essential or not. It does not do this in deciding whether a firm monopolizes an input. Instead, antitrust does this only in considering whether the input denier has a monopoly in the downstream market to which the firm is denying the input (another quirk of antitrust law that will not be considered further here because blanket bans on self-preferencing would not require such a downstream inquiry into monopoly power).

With respect to the question whether an input is monopolized, antitrust instead takes a holistic approach, sometimes asking whether the input is an “essential facility,” for example. Indeed, the proposed self-preferencing legislation eschews the market definition approach, instead prohibiting self-preferencing by those who are a “critical trading partner,” defined to mean those who have “the ability to restrict or impede . . . the access of a business user to a tool or service that it needs to effectively serve its users or customers.”

That’s pretty broad language.

The reason antitrust has always been so vague about what constitutes an essential input is that antitrust recognizes that because every input is unique, every input has a downstream firm for which it is essential.

Must an Input Be Something that You Buy?

One might also object that I have been using “input” in rather a peculiar way here, because I have called the buyer the input supplier whereas an input ought to be something that is sold, not bought. The eraser tip suppliers in my example do not buy the pencil company’s pencils. They sell eraser tips to the pencil company and are paid for doing so. In what sense does a pencil company’s refusal to buy eraser tips from some suppliers count as denial of the pencil input to those suppliers?

The answer is that the proper definition of input—the one that corresponds best to our intuition regarding the injustice of input denial—is not “a thing you buy to use in production” but rather “a thing that is necessary for you to do business.”

This broader definition is necessary to prevent clever changes in the locus of product assembly from undermining the antitrust laws. Consider eraser tips again.

I could equally have told the story of an eraser-tip company that purchases pencils, adds eraser tips to them, and then sells the bundle to consumers. In this case, it would be crystal clear that the pencil is the input and the pencil company’s decision not to supply pencils to the eraser tip company would be input denial. In this telling, the eraser tip company would be injured, just as before, by the fact that the pencil company decided either to make eraser tips in-house or to supply pencils to other eraser tip companies seeking to sell eraser-tipped pencils downstream to consumers.

Why should the pencil company be considered any less of an input denier if it were instead to decide to assemble eraser-tipped pencils itself and to start buying eraser tips from eraser tip manufacturers, though not from the eraser tip manufacturer that it targeted before for input denial? The harm to the eraser tip maker is the same, because either way that company is prevented from getting its eraser tips to consumers on the ends of pencils manufactured by that pencil company.

What matters to antitrust here is not how the eraser-tipped pencil makes it to consumers—whether by being assembled by the pencil company or the eraser tip company—but only that a decision of the pencil company not to do business with a particular eraser tip manufacturer harms the eraser tip manufacturer.

The Inevitability of Power and Suffering in Production and Life

And harm the eraser tip manufacturer it does.

But, as I have explained, that does not matter—indeed, cannot matter—unless it makes for a worse end product served up to consumers, because every act of combining two components to make a new product involves a choice regarding which components to join and which not, and so involves a decision to exclude some component makers from the business and not others. Thus the process of product design, production, and creation is always an exercise of power and the infliction of harm.

This, I think, is why it is so difficult to come to antitrust from the left.

Because progressives are uncomfortable with power and the infliction of harm. Progressives want that to go away. But it turns out that everything—everything—they have is inescapably a product of the exercise of power and the infliction of harm.

You cannot build, you cannot create, you cannot make, without choosing—rejecting some additions and embracing others—and each such decision destroys someone’s business (at least to a small extent) and leaves someone out in the cold, if not physically, then socially and mentally.

It would be nice to be able to avoid this ugly scene in which private firms make private decisions about how to make things, hurting each other along the way, and instead to commit all such decisions to the public—here the market, meaning consumers. This is the market option—to just sell all the components directly to consumers and let them decide which should be used and which not.

But the public has trouble enough selecting a President every four years. It does not want, nor does it have the intellectual capacity, to decide how everything is to be made.

And even then harm and the exercise of power could not be avoided, for the public would still have to decide. Consumers might not like Acme Eraser’s eraser tips and so not buy them to put on their pencils. And so Acme would be denied an essential input—a market—and wither as a result. We might, for the moment, think it more just that the public carry out these executions, as opposed to private firms.

But if you really are concerned about the wielding of power and the infliction of harm, then you should not much care who is doing the wielding and the inflicting, but abjure it all.

Thus input denial forces on the progressive the need to come to terms with the inevitability and pervasiveness of power and suffering in business, and, indeed, once one comes to think of it, in life. For all human behaviors involve choices regarding what to prefer and what to reject, with whom to spend time and with whom not, and so all involve input denial and the infliction of pain to a greater or lesser degree.

The really important question then appears to be not whether to condemn power and suffering but rather how to regulate their deployment and infliction. The question is: who should have the power and who should suffer?

In antitrust, the answer the law currently gives is that firms that make inferior products should suffer, and private firms should decide what combinations of components (i.e., what products) are inferior and what not, except in a relatively small set of cases in which consumers, despite their limited cognitive bandwidth, would do a better job of designing their products.

That, it seems to me, is the right approach, and one that leaves progressives plenty of scope to do good by taking authority from firms and giving it to consumers in cases in which firms produce junk.

Scholarly interest in personalized pricing is growing, and with it confusion about what, exactly, empowers a firm to personalize prices to its customers. You might think that the key is information. So long as you know enough about your customers, you can tailor prices to each. That is, however, incorrect.

No matter how much you happen to know about your customers—indeed, even were you to have a god’s total information awareness regarding each of them—you would not be able to charge personalized prices if you were to operate in a perfectly competitive market. Competition trumps information.

That is because in a perfectly competitive market there are always other sellers available who are willing to charge a price just sufficient to make the marginal buyer in the market willing to stay in the market and make a purchase. If there weren’t, then there would be a chance that the marginal buyer would not be able to find a price that he is willing to pay, and so would not buy, and then the market would no longer be perfectly competitive. For the perfectly competitive market is one in which competition leads to a price at which the marginal buyer and seller are willing to transact.

And so any attempt you may make to personalize a higher price to your inframarginal customers—the ones who are in principle willing to pay a higher price than the marginal buyer—will be met with scorn. Your customers will find those other sellers offering prices keyed to the willingness to pay of the marginal buyer and will purchase from those sellers instead at that marginal-buyer-tailored price.

Thanks to this effect, all buyers will transact at the same, marginal-buyer-tailored price, and so we can conclude that in a perfectly competitive market, price will always be uniform—and uniformly equal to the price at which the marginal buyer and seller transact. (More here.)

It follows that while information is a necessary condition for the personalizing of prices, it is not a sufficient condition.

You also need a departure from perfect competition, which is to say, you need: monopoly. Or at least a hint thereof.

I have argued that personalized pricing is one way to break the iron link between redistribution and inefficiency. When you personalize prices, you can personalize one price to the marginal buyer, ensuring that he stays in the market and the market is efficient, and whatever other prices you wish (within limits) to inframarginal buyers, enabling the redistribution of wealth. But it is important to remember that information on buyers is not alone enough to make this possible. The seller must be a monopolist, too.

Thus the use of personalized pricing as a tool of social justice directly conflicts with the mindless “big is bad” rhetoric that one finds today in certain corners of the progressive movement.

To redistribute wealth at the market level you need to start with big.

And then discipline big’s pricing behavior.

Margrethe Vestager is saying that the Facebook outage shows the need for more competition in social media. And she’s right, if you enjoyed that outage and would like to make it permanent, not in the sense that you will stop getting any social media, but in the sense of crossing half your friends off of your friends list forever. For that is what will happen in a world of “fifty different Facebooks” in which, by antitrust design, you are no longer permitted to belong to the same social media platform to which everyone else belongs.

What the Facebook outage tells us is not that we need more competition in social media; it tells us that we need more regulation. That Facebook is a public utility and if it does not voluntarily pour resources into service quality, as public utilities do, then we must force it to do that.

If Facebook had a smart, Theodore Newton Vail-like CEO, however, the political fallout from this outage would be enough to focus Facebook’s mind. Because firms that understand that they have become public utilities understand that they have become, through and through, political animals, satisfying political constituencies by delivering to them the services they demand, on pain of government intervention.

And that intervention is often intemperate, unreasoning, wrathful antitrust breakup, as indeed eventually happened to AT&T long after Vail, the company’s famous early-twentieth-century CEO—who charmed the public by delivering universal, reliable telephone service—departed. And as the FTC is threatening now.

Indeed, the only rationality about antitrust intervention against a natural monopoly like Facebook is that the anger that drives the intervention makes it a credible threat in spite of its unreason, rather the way that the likelihood that a thug will kill you for the slightest offense—and hence do time, quite irrationally, over nothing—puts you on your best behavior around him. Antitrust intimidates. The FTC intimidates. Vestager intimidates. That doesn’t make them rational in this context, but it does make them useful.

But is competition really irrational here? What about interoperability? Yes, of course we could make Facebook interoperable with other social media platforms. And that would enable us to use one platform to interact with users of other platforms, allowing us to keep all of our social media friends without having to submit to a single monopoly social media provider.

But think, please, about where that would take us: back to the Internet.

That Internet.

The decentralized communications system in which everyone is supposed to own their own server, which sometimes works and sometimes crashes, or rent space on someone else’s, which also sometimes works and sometimes not. And there is some standard-setting body out there promulgating protocols governing communication between these servers, the rules of which are voluntary and sometimes followed and sometimes not followed, enabling the servers sometimes to talk and sometimes not to talk.

It is the world of the bug, of feeling proud that, after five hours of hacking around and reading message boards, or repeated calls to IT, you finally got it to work.

It is the world in which the only reliable, stable mode of digital interaction was: email.

And even that wasn’t all that reliable, because it was the target of avalanches and avalanches of spam, itself a bug of decentralized networking that was only really solved, and then still imperfectly, by the centralization of email service under a single roof—Gmail—enabling a single artificial intelligence to learn to identify and filter the spam effectively.

The whole point of social media, what made us flee from the Internet and embrace Facebook, or its competitors (which social media platform didn’t really matter—it only mattered that everyone embraced the same one, allowing it to substitute for the Internet) was that these platforms weren’t platforms at all in the sense of an open field upon which anyone can play; they were integrated, centralized, organized spaces in which engineers could solve all of the problems of the Internet because they could control the entire space.

That’s right: they were never meant to be platforms; we loved them, from the beginning, precisely because they were walled gardens.

You couldn’t choose your own server or run your own software or handle almost any of your own configurations. And you didn’t have to run some client side program that sometimes made a connection to the network and sometimes didn’t. Facebook did all of that for you, and it was the network, so if you could log into Facebook you always had a connection.

That is what made possible a level of service quality so complete that the recent Facebook crash was memorable in the way that a New York City blackout is memorable: because it is rare (which is not to say that we shouldn’t insist that Facebook do better, just as we insist that the power company do better). It is also what made it possible to have feeds and likes and chat and friends all integrated buglessly into a single place.

The desire for interoperability is the desire to return to the Garden of Internet of the 1990s, the one we left because it wasn’t, actually, Eden.

And if you think misinformation is bad on Facebook, just imagine what it will be like when there are “fifty different (interoperable) Facebooks” and no central authority capable of deciding who can interoperate and spread news and who cannot.

(A potential saving grace here is that interoperation will be so clunky and bug prone, social media communication so degraded as a result of interoperability requirements, that the loss of the ability to regulate speakers will be offset by the slowdown in the speed with which misinformation is able to spread. We didn’t see misinformation as a threat on the old Internet because it was so much harder to communicate.)

Well, why can’t we have it both ways? Decentralize the administration but mandate the protocols and service quality and so on? The answer is: of course we can. But if we’re going to regulate all aspects of service, and hence retain the centralization of social media through the medium of the government rather than a private corporate entity, wouldn’t it be easier to, um, just regulate Facebook?

But that would deny us the pleasure of killing it.

The election of a longtime Washington insider to the presidency was, if anything, supposed to mark a return to competent, reality-based government. The astonishing failure of the administration to predict—or adequately plan for—the rapid collapse of the Afghan government this summer is hinting that the new administration is not all that much more competent than the last.

There are warning signs in Biden’s antitrust policy as well. His executive order on competition, for example, misleadingly cited as authority academic sources that either didn’t support the order, or suggested it would fail. And now we learn that the administration actually thinks it can use antitrust action to reduce inflation caused by pandemic-induced supply chain disruption. Oh my.

Antitrust won’t stop inflation caused by supply chain disruption because the profits that firms generate from supply chain disruptions are scarcity profits, not monopoly profits. They are the product of actual scarcity, not the artificial scarcity that antitrust can alleviate by promoting more competition. Only an administration that doesn’t know its Antitrust 101 would miss this.

Indeed, competent progressivism doesn’t make these kinds of mistakes. Take John Maynard Keynes. He was all for killing off the rentier—the earner of the kind of economic profits that supply-chain-induced inflation is dealing to many corporations these days—but he never thought antitrust would do the trick.

Because, like most progressives of his generation—and the competent progressives in ours—he understood that rent is a problem of competition, not monopoly.

The rentier doesn’t need to smash his competitors; he just lies on his fainting couch and watches the numbers tick up in his bank account because he happens to own a uniquely productive resource, one that competitors can’t beat, even if competitors are allowed to try their hardest.

Similarly, the big corporations charging high prices today don’t need to smash their competitors to charge those prices, because their competitors don’t have access to better sources of supply either. No matter how hard these firms compete with each other, there is just not enough production capacity in the supply chain to enable them to ramp up output and therefore no firm has an incentive to reduce prices and increase profits through increased market share.

That is not to say that these corporations are not earning rents, meaning profits in excess of what they need to be ready, willing, and able to produce and sell their wares on the market. They are. Rental car companies, for example, are charging multiples of what they used to charge for a car, while at the same time facing much lower costs than they ever did, because they are unable to expand their fleets. It follows that the price premia rental companies are charging are pure profits that the rental companies do not strictly need in order to remain in business.

But the profits are not a result of anticompetitive conduct. They are due, instead, to shortage. The rental car companies are not expanding their fleets, because a microchip shortage means there aren’t any cars available for them to buy. So, while they wait, the companies ration access to the cars that they do have by charging high prices for them, ensuring that those consumers with the largest pocketbooks get access to cars, and those with less means have to sit on the sidelines and wait for the shortage to end.

Unless it is reformed to adopt pricing remedies—and there is no indication the Biden Administration is seeking to do that—Antitrust has nothing to bring to this situation but trouble. To the extent that Biden’s antitrust initiatives translate into actual cases and the imposition of actual antitrust remedies, we can expect costs that will be passed on to consumers in every competitive market that the Administration mistakenly targets. The costs will be legal costs and also those associated with unnecessary remedies—the firm that actually worked better when it was whole hacked to peaces to please the angry antitrust god.

But the biggest danger posed by the use of antitrust to deal with supply chain disruption is that antitrust will be completely ineffective at actually getting prices down.

Smash three big rental car companies into twenty small ones, but you still won’t increase the number of available cars, and so you won’t, actually, increase competition, or bring prices down. Each of the smaller companies will know that it can raise prices without losing market share to the other nineteen, because the other nineteen don’t have any additional cars to rent out to customers either.

Failing to get prices down would be bad, however, because prices can and should be made to come down. For, as noted above, the fact that prices are currently high due to shortage does not imply that they must be high in order to induce firms to continue to compete and produce as best they can. The rental car companies could just as easily cover their costs by charging the rock bottom prices they charged last summer because the companies are, after all, still fielding the same fleets they fielded last summer. They are charging higher prices because the shortage (but not their own anticompetitive conduct) shields them from additional competition.

How, then to get prices down without antitrust? Keynes’s elegant solution was the euthanasia of the rentier. This was understood by Keynes to mean that the central bank could use monetary policy to drive down interest rates, thereby depriving the rentier of the ability to earn a fat return on his investments.

But the euthanasia of the rentier actually has a deeper meaning. For an actual rentier could always respond to low interest rates in financial markets by using his money to invest directly in actual businesses, especially businesses earning large rents due to shortages. What makes this impossible, and really does euthanize the rentier, is that the lower interest rates created by monetary policy induce large numbers of businesspeople to borrow money and invest it in new businesses, and this investment ultimately eliminates shortages across the economy, driving rents down and killing off the rentier.

But it takes time for money invested in new businesses to eliminate shortages and drive prices down. To get prices down now, before supply-chain disruptions can be eliminated, there are two other options.

The first is direct price regulation. Government could impose price controls in industries subject to pandemic-driven supply chain disruptions. President Biden could order rental car companies to revert to charging their low summer 2020 prices, for example. President Nixon imposed price controls in the 1970s; it can be done.

The second is taxation. Congress could vote a special corporate tax aimed at hoovering up the rents generated by firms enjoying pandemic-driven shortages. That would not bring respite directly to consumers, who would continue to pay high prices, but Congress could vote to redistribute the proceeds of the tax to deserving groups, or spend the money on projects like infrastructure that benefit everyone, rather than leaving it to firms to pay the proceeds out to wealthy shareholders to stimulate the market for yachts.

I am having trouble deciding whether the Biden Administration’s obsession with antitrust as cure-all is the legacy of President Biden’s long career as a centrist Democrat or a result of the meathead radicalism that the Trump Administration inspired in some progressives.

Either way, like relying on the Afghan government to defend Kabul, he can’t say no one warned him it wasn’t going to work.

Real Progressive Antitrust

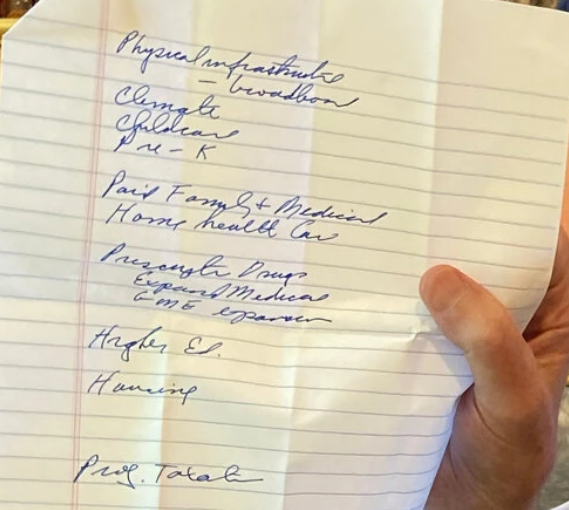

Notice what’s missing from the agenda of the only self-described democratic socialist in the U.S. Senate:

Everything on the Sanders agenda is about spending (read transfers), to be paid for with progressive taxation. Scattershot interpersonal redistribution via competition? Not so much.

The contrast with President Biden and his 72-point competition cure-all couldn’t be starker.

President Biden’s Executive Order on Promoting Competition in the American Economy does a great job of targeting a range of business practices across the economy that harm workers and consumers.

But the order—and the fact sheet accompanying it—also highlight how much wishful thinking is currently going into the contemporary progressive romance with competition as an economic cure-all.

The fact sheet declares that economists have found a link between competition and inequality, even though whether a link exists remains the most important open question in antitrust economics today and the subject of much ongoing debate. And despite the competition rhetoric, most of the order is actually about consumer protection or price regulation by other means, not competition.

Wishful Thinking about Competition and Inequality

Anyone who has been following the unresolved debate over the existence of a link between competition and inequality is going to be surprised to learn from President Biden’s fact sheet that “[e]conomists find that as competition declines . . . income [and] wealth inequality widen.”

The surprised might include Thomas Piketty, the dean of the contemporary economic study of wealth inequality, who has observed that the fundamental cause of inequality “has nothing to do with market imperfections and will not disappear as markets become freer and more competitive.”

But it might also be news to the authors cited by the fact sheet itself.

Follow the first of the quoted links and you get to a paper that connects the decline in labor’s share of GDP (a proxy for inequality) to rising markups (firms charging higher prices relative to their costs), but not to a decline in competition.

The author is careful not to link rising markups to a decline in competition because increases in markups have two potential causes, not one: monopoly power and scarcity power—as I have highlighted in a recent paper.

That is, firms can obtain the power to jack up prices by excluding competitors and achieving monopoly power, or they can do it by making better products than everyone else (or the same products at lower cost), in which case even the price prevailing in a perfectly competitive market will represent a markup over cost.

The great open question of contemporary antitrust economics is whether the evidence of an increase in markups in recent years is evidence of monopoly markups or scarcity markups. As Amit Zac has pointed out to me, this is the essence of the disagreement between the work of De Loecker et al. (monopoly markups) on the one hand and the work of Autor et al. (scarcity markups) on the other.

The point is: this is an unresolved question. Economists haven’t “found” a connection between declining competition and contemporary increases in inequality. They haven’t even found a connection between declining competition and contemporary increases in markups. They’re still looking.

But you wouldn’t know that from the fact sheet.

Follow the second of those links and the support is equally weak. The title of the cited article, “Inequality: A Hidden Cost of Market Power,” would no doubt appeal to a fact sheet writer fishing Google for quick cites. But the paper itself could not be more timid about its conclusions, telling readers that it does no more than to “illustrate[] a mechanism by which market power can contribute to unequal economic outcomes” and warning that “[a]lternative models and assumptions may yield different results.”

The authors have good reason to be timid, because the paper’s attempt to distinguish between monopoly markups and scarcity markups extends no further than this: “we attempt to compare actual mark-ups with the lowest sector specific mark-ups observed across countries, in order to estimate an unexplained or excess mark-up.”

So: find the lowest markups in an industry, assume they are scarcity markups, and attribute any markups you find that exceed them to monopoly.

Not exactly convincing, as the authors themselves seem to telegraph—which is why the character of the higher markups we are observing today very much remains an open question.

Highlighting Antimonopolism’s Intellectual Deficit

The last revolution in antitrust policy happened in the 1970s, and however one might feel about the path it beat toward less antitrust enforcement, there is one thing one must grant: it carried the day as an intellectual matter.

You can’t read the book of papers produced by the epochal Airlie House conference and not get the impression that the Chicago Schoolers really got the best of the old antitrust establishment on the plane of ideas. I once asked Mike Scherer, who carried the banner for the old pro-enforcement establishment more than anyone at that conference, why he comes across as so timid in the dialogues reproduced in that book.

His answer: Chicago had convinced him, too.

The current inflection point in antitrust has not been built on anything like that level of intellectual consensus. I have argued elsewhere that this is because the current movement didn’t need to win the academy to achieve liftoff, as Chicago did. The current movement got its thrust instead from a highly sympathetic press, which has a competitive interest in unleashing a reinvigorated antitrust on its nemeses, the Tech Giants.

It is a symptom of contemporary antimonopolism’s intellectual deficit that our new, self-consciously reality-based administration can go to war against monopoly only by passing off economic conjecture as economic fact.

Did Golden-Age Antitrust Drive Postwar Economic Growth and Save Consumers “Billions”?

Before moving on from the order’s wishful thinking, I can’t help but also mention the fact sheet’s claim that mid-20th-century antitrust “saved consumers billions in today’s dollars and helped unleash decades of sustained, inclusive economic growth.”

Was mid-20th-century antitrust enforcer Thurman Arnold responsible for America’s 2% annual growth rate from the 1950s to the 1970s?

The press release doesn’t cite any economic study taking that position—because there is none. But there are plenty that think those twenty years of 2% growth had something to do with the nation’s return to the peacetime production possibilities frontier after nearly two decades of depression and war.

And did mid-20th century antitrust really save consumers “billions?” You might be forgiven for thinking that link leads to a recent economic study. Instead, it is to a set of figures, released by Thurman Arnold himself, that are cited by legal historian Spencer Weber Waller as possible exaggerations. For example, Waller: “[Arnold’s] case against the milk industry in Chicago supposedly produced $10,000,000 a year in consumer savings” (emphasis mine).

All the figures cited by Waller do probably add up to billions in today’s dollars. But Waller cited them as evidence that Arnold knew how to use hyperbole to win political support for his antitrust campaigns.

Not that the Biden Administration would be doing the same thing.

Competition as Price Regulation by Other Means

But what about the order itself? Here’s where things really get interesting. For despite the rhetoric little of it is actually about competition: it is, amazingly, largely about price regulation and consumer protection instead.

Why? Because the competition business and the inequality business are two very different things; and no matter how hard you tell yourself you are doing competition policy, if you’re trying to equalize wealth, you’re going to end up doing something else.

To see why the order is mostly about price regulation, consider that competition really has two virtues, one more important than the other. The smaller virtue is that competition can reduce prices. The greater virtue is that competition promotes innovation, which is the principal driver of economic growth and benefits to workers and consumers alike.

The reason competition’s effect on prices is a lesser virtue is that competition is wasteful. It means duplication of management and often diseconomies of scale. As I have argued at length elsewhere, if you want to get price down it’s far less expensive simply to order lower prices than to try to jerryrig markets into producing them through unregulated competition.

Antitrust gets this, and so it does not actually prohibit the charging of high prices. Antitrust is much more interested in prohibiting conduct aimed at excluding competitors from markets, because this keeps out the sort of innovative challengers that are responsible for the link between competition and innovation.

The striking thing about Biden’s order is that it is mostly aimed at promoting the first kind of competition—competition meant to lower prices—rather than the second.

Which makes it price regulation by other means. Let’s consider some of the initiatives contained in the order.

Canadian Drugs

The order calls for lowering prescription drug prices by importing drugs from Canada. The thing is: the drugs imported from Canada will be the same as drugs sold in America, only cheaper, which means that the only competition this will create will be between the same products sold at different prices on different sides of the border.

Promoting competition between iterations of the same product produced by a single producer isn’t going to promote innovation. It’s just price regulation by other means.

And wasteful means at that. There’s a reason why Canada has lower drug prices than the U.S., and it’s not because there’s more competition in Canada—a lot of Canadian drugs come from America in the first place. It’s because Canada regulates drug prices directly.

So why can’t we just do that, too, instead of sending American drugs north to be price regulated so that we can bring them back down south at lower prices?

Because, I guess, that wouldn’t sound like a competition policy solution, and progressives today are convinced that competition cures all.

Generic Drugs

The order also simultaneously calls for more antitrust enforcement against “pay-for-delay” drug patent settlements and “more support for generic and biosimilar drugs.”

As in the case of drugs from Canada, competition from generic drugs doesn’t promote innovation. Generics are, by definition, copies of preexisting drugs; generic drug companies don’t invent new drugs, they just strive to bring old ones to market at low prices. So generic competition is just price regulation by other means, and particularly futile and inefficient means at that.

For branded drug companies use pay-for-delay settlements to undermine generic competition, and enforcers have wasted untold hours litigating to stop them, to only modest effect. Plus, forty years after Congress embraced generic competition with the Hatch-Waxman Act, we still have a drug price problem.

That makes an order telling the agencies to stop pay-for-delay and to promote generic competition at the same time more than a little odd. It is like telling a fireman to pump harder and stop more leaks. It might be time to find a different hose.

If Congress wants to get drug prices down, the easiest way to do it would be to follow the Canadians and, you know, order drug prices down, rather than trying to manage the Herculean task of creating and maintaining a competitive generic drug market. The Biden Administration should call for that.

But competition cures all.

The Right to Repair

The order also calls for protecting the right of buyers to repair a host of items from cell phones to tractors.

Now, one can imagine that competition between repair shops might lead to innovation. But it will be innovation in repairs, which is not going to do much to raise living standards. The innovation that matters is not in repairs but in the design of the products being repaired.

Opening products up to third-party repairs isn’t really about competition at all, therefore, but about price regulation by other means.

And not regulation of the price of repairs, but rather of the price of the product to be repaired. The Biden Administration probably believes that making products reparable will drive down the all-in price that buyers pay for the products, because buyers will be able to avoid paying high repair fees to manufacturers, or will be able to go for a longer period before having to replace the item with a new one.

But if manufacturers are able to extract extra revenues from their buyers by charging them for repairs today, what’s to stop them from simply raising their up-front prices to compensate for lower revenues on repairs tomorrow?

If the Biden Administration thinks cell phones and tractors are too expensive, a better way to actually reduce the amount people pay for these products would be to order manufacturers to charge lower all-in prices for them.

But competition cures all.

Small Business Procurement

The fact sheet says that the order will “[i]ncrease opportunities for small businesses by directing all federal agencies to promote greater competition through their procurement and spending decisions.”

But “competition” here means the opposite of what we normally mean. It means that the firm offering the best products at the lowest prices shouldn’t get the contract; the smallest firm should get it instead, even if it offers shoddy products at high prices.

This is regulation of the price paid by government for goods and services by other, deeply inefficient means.

Here’s a better way to redistribute wealth from taxpayers to small businesses that can’t make it in the market: just write their owners checks to stay home. That way the (presumably) poor get their money without the federal government having buy anything but the best.

But competition—or its semblance—cures all.

Protecting Third-Party Sellers on Amazon

The order also directs the FTC to create rules for “internet marketplaces” and the fact sheet suggests that the rules should prevent Amazon from copying the products of third-party sellers.

As the use of generic competition to tame drug prices suggests, the sort of competition that comes from copying is primarily about getting prices down, rather than innovation. If Amazon wanted to beat its third-party sellers by innovating, it wouldn’t create close matches of their products, but rather something new. By selling an identical product, Amazon instead places all the competitive pressure on price.

So we can understand rules preventing Amazon from copying as attempts to drive the price of goods sold on Amazon’s ecommerce platform up, presumably to redistribute wealth from consumers to third-party sellers. Such rules are, in other words, price regulation by other means.

Because the rules would drive prices up, they are the least consumer-friendly initiative described in the fact sheet (unless one expects Amazon to respond by competing more with its third-party sellers based on innovation).

But precisely because the rules seek to drive prices up rather than down—to squelch duplicative and wasteful competition between Amazon and third-party sellers rather than to promote it—they are also the order’s least inefficient example of price regulation by other means.

But they represent price regulation by other means all the same.

Non-Competes

According to the fact sheet, the order “encourages the FTC to ban or limit non-compete agreements.”

Non-compete agreements in high-skilled jobs are associated with higher wages, suggesting that at the high end they help firms invest in their employees, and that investment, in leading to new skills and abilities, counts as a kind of innovation in human resources.

But the fact sheet is interested in the application of non-competes at the low end: to “tens of millions of [presumably ordinary] Americans—including those working in construction and retail . . . .” Here, the evidence suggests that non-competes don’t induce firms to invest more in their employees; they just prevent employees from using outside options to bid up their pay.

A ban on non-competes for ordinary Americans would therefore not have any effect on innovation in worker training, but it would raise wages, making it price regulation by other means.

If we really want to get wages up, of course, the way to do it is to order them up, through initiatives like an increase in the minimum wage. And I get that the Biden Administration indeed also wants to raise the minimum wage.

But that doesn’t make banning non-competes any less price regulation by other means.

Direct Price Regulation

To President Biden’s credit, the order also calls for plenty of direct, and therefore more efficient, price regulation. The remarkable thing is that he does this in a competition order.

The Federal Maritime Commission is to protect American exporters from “exhorbitant” shipping charges. Railroads are to “treat . . . freight companies fairly,” which means charging them lower prices for access to track. The USDA is to “stop[] chicken processors from . . . underpaying chicken farmers.” The FCC is to “limit excessive early termination fees” for internet service. And airlines are to refund fees for wifi or inflight entertainment when the systems are broken—a regulation of the all-in price of a flight.

(Ok, the reason the order doesn’t do more direct price regulation might be that the requisite statutory authority to act in other areas is lacking. But I’m not aware of any Administration calls for Congress to pass new price regulatory legislation, apart from raising the minimum wage and adopting reference pricing in drugs, which latter would apply only to Medicare.)

Consumer Protection

The amount of price regulation—of both the wasteful, competition-mediated sort and of the direct sort—in this order is rivaled only by the amount of consumer protection.

Hospital price transparency is to be fostered, surprise billing condemned. Airline baggage and cancellation fees are to be clearly disclosed. The options in the National Health Insurance Marketplace are to be standardized to facilitate comparison shopping. So too broadband prices.

The common thread to all of these initiatives is that they correct cognitive limitations of consumers that make it difficult for them to find the best, lowest price options on the market, and so leave them poorer. That’s why I class them as consumer protection initiatives, and why they are a good thing.

Consumer protection is competition-adjacent policy—competition does work better, and firms may be more likely to innovate, when consumers have good information about the products offered by competing firms. But the main focus of these initiatives is on empowering consumers to avoid paying out more cash than necessary for goods and services.

Like the price regulation initiatives, it’s directed, ultimately, at the distribution of wealth, not competition. Which is why it is surprising to find so much consumer protection in a competition order.

Unions and Occupational Licensing

The focus on price regulation and consumer protection are a welcome surprise. But the dangers for progressives of confusing these things with competition policy are also on display, for competition is just as likely to be the enemy of equality as it is to be its friend, and it is very easy to lose sight of this when pursuing an equality agenda in competition terms.

Thus in a press release that is already pretty deaf to irony, this takes the cake: “the President encourages the FTC to ban unnecessary occupational licensing restrictions [and] call[s] for Congress to . . . ensure workers have a free and fair choice to join a union . . . .”

Here’s a secret about those “unnecessary licensing restrictions”: they’re state-created unions. The only difference between them and actual unions is that they operate by restricting labor supply, and thereby driving up wages, whereas unions operate by driving wages up, and thereby restricting labor demand. If you’re against occupational licensing because it makes it hard to get a job, you should be against unions, and if you’re in favor of unions because they drive up wages, then you should be in favor of occupational licensing.

The way to minimize mistakes in fighting inequality is to focus on fighting inequality.

Indeed, one cannot help but feel that this order, despite being well-intentioned and expansive, is a sideshow to the real work of fighting inequality that the Administration has undertaken on the tax side. Given the breadth of applicability of the corporate tax—all industries are swept in at once—and the power of the corporate tax to target the proceeds of excessive pricing directly, last week’s agreement of 130 nations to a global minimum corporate tax will likely do far more to divest firms of their markups than anything in today’s order—even were it all implemented as direct price regulation.

The most important charge against the Tech Giants is that they are creating kill zones: no one wants to create new online functionality that Google or Facebook in particular might easily copy. Whether kill zones exist remains a subject of debate, but that hasn’t stopped antimonopolists from wanting to respond anyway by breaking up the Tech Giants.

But there’s a treatment that is more likely to cure the disease without killing the patient—one which has the added benefit of helping us determine whether there actually is a disease to begin with.

But first, let’s consider why kill zones would be a problem if they really do exist.

If kill zones exist, then startups won’t introduce innovative social media functionality into the market because they will know that if Google or Facebook copy it, consumers will prefer the Google or Facebook versions—because those versions will be integrated seamlessly into the rest of the functionality those companies offer—and so the startups will lose out in the market. But because the startups won’t introduce the new functionality, Google and Facebook will feel no need to introduce it either, and so the functionality never makes it into our online lives.

The saga of Vine, Twitter’s erstwhile video sharing service, provides a nice illustration of the kill zone argument. Vine pioneered the video sharing format, but just as it looked poised to take off, Facebook introduced essentially the same functionality in Instagram, and because Instagram was already much bigger, social media users found it easier to embrace the format in Instagram than by migrating over to Vine. The lesson of that episode for someone with a bright idea for the next big thing in social media is: don’t waste your time. So long as it’s something that the Tech Giants can copy, they will, and they’ll win.

To be sure, TikTok shows us that innovation is still commercially viable in social media, the Tech Giants notwithstanding. But the key to TikTok’s success is the algorithms it uses to target videos to users, and those are not easy for the Tech Giants to copy. That means that major, irreproducible innovation is still possible in this space.

But not all good ideas that make our lives better are necessarily major, irreproducible technological steps. If there hadn’t been a Vine, video sharing might have taken a lot longer to invade social media, and that would have been a loss to users, many of whom love the format.

So what to do about kill zones?

I am often struck in reading Nick Lane’s excellent books on biochemistry (Power, Sex, Suicide, and The Vital Question are my favorites) by how much more careful biochemists seem to be in diagnosing problems and sussing out solutions than we are in antitrust. All the more struck, in fact, because biochemistry is a more mechanistic, indeed, easy, field than is antitrust.

In biochemistry, the basic repertoire of behaviors of the smallest units of analysis—molecules—is known with absolute certainty, thanks to the laws of chemistry and quantum physics. If molecule A hits molecule B, we know exactly what will happen. And hypotheses in biochemistry are often testable: you can find a thousand or ten thousand living human bodies in which to observe the biochemical behaviors that interest you.

By contrast, in antitrust, the basic repertoire of behaviors of the smallest units of analysis—human beings—is almost infinite and the subject of perennial debate. We like to assume rational, profit maximizing behavior, but we know, thanks to decades of behavioral economics, that actual behavior is much, much more complex and varied. And hypotheses in antitrust are almost impossible to test on the scales required to produce real knowledge: where do you find ten thousand similar markets to deconcentrate in order to determine whether breakup actually works?

You would expect, then, that antitrusters would be even more careful in diagnosing problems and sussing out solutions than are biochemists. But instead the sheer complexity of the problem seems to impel us in the other direction. It tempts us to boil away the complexity and then find clarity in a residue that bears little resemblance to actual markets. (For the record, I am as guilty of doing this as the next antitrust scholar.)

We should take a page from biochemistry and recognize that while kill zones sound plausible, plausibility is not reality, and so any solution to the kill zone problem must include, as a precondition, some attempt to determine whether there really is a problem. We need to diagnose.