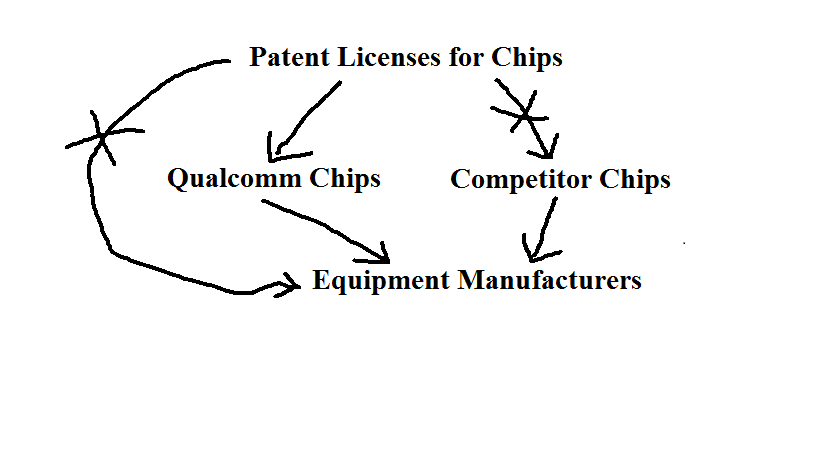

The district court’s opinion in the Federal Trade Commission’s case against Qualcomm is 233 pages long, but it really comes down to a single diagram. Because the case is really just this: that Qualcomm excluded rival chip makers from the market by refusing to license patents either to rivals for bundling with their chips or to chip buyers so that the buyers could assemble the bundle on their own.

The licenses are for “standard-essential patents,” meaning patents necessary for chip buyers, who manufacture cell phones, to make phones that comply with industry standards. Chip buyers must, therefore, acquire the licenses to function. Qualcomm sold licenses in a bundle along with its chips, but refused to sell them any other way, either directly to cell phone makers who might want to combine them with chips purchased from Qualcomm’s chip-selling rivals (the “no license no chips” policy), or to rival chip makers who might want to bundle them with their own chips and sell them on to cell phone makers. That made the chips supplied by rival makers undesirable to cell phone makers, because the rival chips did not come with patent licenses and the cell phone makers could not obtain those licenses independently.

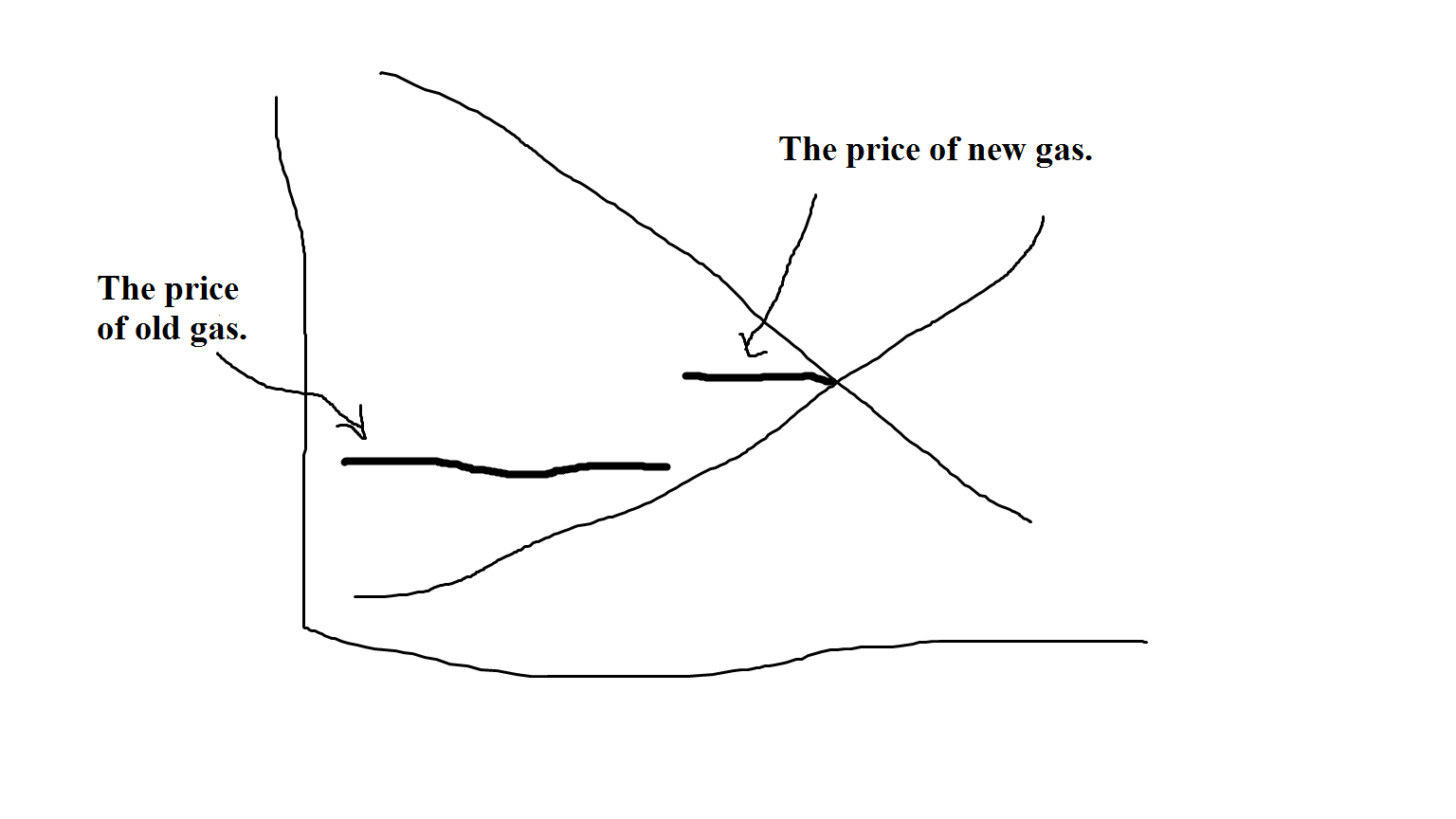

The diagram describes a supply chain, with patent licenses, which amount to an essential input into the production a usable chip product for cell phone makers, at the top of the chain. Cell phone makers must acquire both this input and chips themselves to function. The second, middle, level in the supply chain is the physical chip itself. Qualcomm competes in this market, and uses its control over the essential patent input to exert power over rivals in this market. Cell phone makers are just as happy buying licenses and chips separately and assembling them on their own, or buying licenses bundled with chips. Qualcomm excludes rival chip makers by making it impossible for either rival chip makers or cell phone makers to acquire the license and bundle it with rivals’ chips.

The diagram reflects this by putting Xs through supply arrows leading from patent licenses directly to cell phone (“equipment”) makers and from chip patents to rival chip makers. Because Qualcomm nixed these supply routes for patent licenses, the only way for cell phone makers to obtain licenses was through purchases of Qualcomm chips. Because cell phone makers couldn’t get the licenses independently or through rival chip makers, they had no reason to buy chips from rival chip makers, wiping out those rivals of Qualcomm in the chip market.

Analogy to Pencils and Erasers

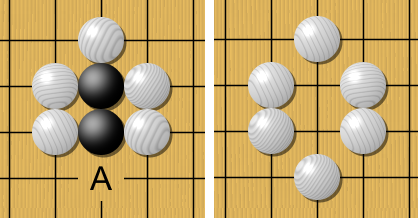

It’s as if a pencil manufacturer that also happened to be the world’s exclusive producer of erasers were to refuse to supply erasers to competing pencil makers and also refuse to sell them directly to consumers. The only way to obtain an eraser for use with a pencil would be to purchase an eraser-tipped pencil from the pencil manufacturer. Competing pencil makers would be unable to compete, because most pencil users want to be able to erase.

Actually, the case against Qualcomm is a lot clearer than would be the case against this hypothetical pencil conduct. What ultimately drives antitrust liability in single firm conduct cases is whether the input supplier’s decisions about how to route supply results in an end product that is ultimately better for buyers than alternatives. The inputs here are the patent licenses, and the question is therefore whether Qualcomm’s insistence on only supplying licenses alongside its own chips made those chips better.

The answer has got to be no: a patent license is just a piece of paper– really, just an idea–the guarantee that the licensor won’t sue for infringement. Combining this bit of ephemera with the chips creates no value greater than the sum of its parts. It doesn’t make the chips run faster, or sip less power, or process more data. It adds nothing at all to the product sold by Qualcomm. Cell phone makers can do just as good a job combining the license with Qualcomm’s chips as can Qualcomm, and rival chip makers can do just as good a job combining the license with their chips as can Qualcomm.

By contrast, the pencil maker might be better at affixing erasers to pencils than any other firm in the business, or indeed than pencil consumers, in which case the pencil maker’s insistence on reserving its entire eraser supply to itself might actually make consumers better off. The pencil maker can defend its decision not to treat erasers as a standalone component and supply it to others as necessary for it to improve its end product. Qualcomm just can’t make that kind of argument.

So Qualcomm should lose on the economic merits. Buyers suffer the harmful consequences, in the form of higher chip prices, that come from Qualcomm’s freezing-out of rival chip makers. But buyers enjoy none of the advantages in the form of improvements in the quality of the product offered by Qualcomm, because no such improvements follow from Qualcomm’s bundling of licenses with chips.

At least, the economic case is clear before you take into account that licenses are not normal production inputs, but rather government-granted rights of exclusivity the purpose of which is to aid the grantee in excluding competitors from markets. Patents fail by design to add anything to the products with which firms combine them. Their whole purpose is to exclude, nothing more. Treating a firm’s decision to license only its own products as monopolization in violation of the antitrust laws simply because the license does nothing to enhance the value of the product would make all exercises of patent rights illegal monopolization.

The Importance of the Standards Context

If a refusal to license patents were all there was to this case, the FTC would surely not have brought it. What makes this case special is that Qualcomm’s patents are essential inputs into chip production only because standard-setting bodies chose to incorporate Qualcomm’s patented technologies into industry standards. This matters, because we respect the monopoly power created by a patent only because we assume that it derives from the fact that the patented technology represents an innovation that competitors have failed to match. We assume that what makes a patent necessary for competitors to be in the market is that the patent covers some invention that makes the product better. The patent, and the monopoly power that flows from it, then serves to reward innovative activity, creating incentives for all firms to innovate and improve their products.

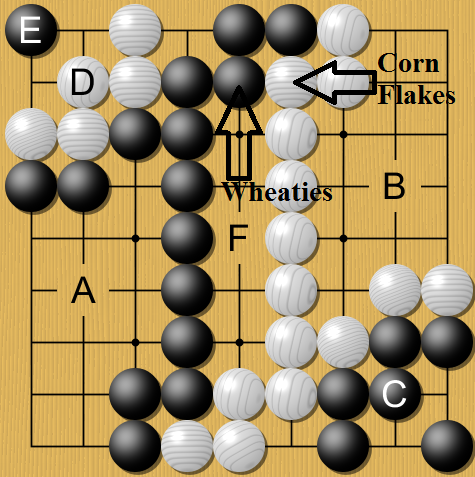

But when a patent is a necessary input because a standards body has incorporated it into an industry standard, we cannot be sure that the patent’s essentiality ultimately derives from the fact that the patented invention is better than alternatives. Standard setting bodies often have a menu of technologies that they may incorporate into a standard, each of which is equally innovative and equally suited to accomplishing a given task. That is to say, standard-setting bodies often choose from a menu of competing technologies, none of which is essential precisely because other technologies on the menu accomplish the same task. The standards body must choose only one technology, however, because that’s the point of establishing a technical standard, and it is that step of adopting the technology for the standard, and not the technology’s superiority or uniqueness, that makes the standard essential. All the firms in the industry must adhere to the standard, and the decision of the standards body therefore eliminates all competing, equally innovative technologies, from the field.

The source of the technology’s essentiality, of its ability to confer monopoly power, is therefore the decision of the standard setting body to use the technology, not the fact that the technology is superior to other existing technologies. That eliminates the basic rationale for which the antitrust laws usually allow patent holders to refuse licenses to competitors. The monopoly power that results cannot, in the case of standards-essential patents, be assumed to reward superior performance. It follows that in this unique context, it is proper to proceed to the next step of asking whether a patentee’s decision to lock up access to its patents does anything to improve the products it sells, and to conclude from the fact that it cannot that consumers are harmed.

The Prior Dealings Wrinkle

While the case against Qualcomm is therefore clear as an economic matter, it is less clear as a legal matter. The trouble is that Chicago School influence over the antitrust laws has restricted the ability of the courts to decide antitrust cases on the economic merits. The Supreme Court’s Aspen Skiing and Trinko cases suggest that a firm’s decision to lock others out of its supply chain (as Qualcomm has done in effectively supplying patent licenses only to itself in its production of bundles of chips and licenses for sale to cell phone makers) can violate the law only when the decision represents a termination of a prior profitable course of dealing.

That is, unless the firm has a history of voluntarily supplying the input (here patent licenses) to competitors, the firm’s decision not to supply the input cannot violate the antitrust laws.

Thus when a termination of a prior profitable course of dealing does exist, the courts are free to get to the economic merits and decide whether the termination made the product better. But when a termination does not exist, the courts must kill the case, even if the termination does nothing for the product, and therefore must harm consumers. So much is true, at least, if the Supreme Court really meant this to be a hard and fast rule of law. Courts see the existence of a termination as a signal that the firm’s refusal to deal might be motivated by anticompetitive intent, and that is in turn some evidence that the move does not improve the product. Rather than parse through all cases looking for product improvements or the lack thereof, courts prefer to devote their attention only to those in which the existence of a termination suggests that a lack of product improvement is likely. The courts assume that the rest of the cases involve benign, product-improving, conduct.

The FTC has tried to get around this problem by arguing that Qualcomm’s contractual commitment to license its patents to rival chip makers, which Qualcomm made as part of its participation in the organizations that set cell phone standards, amounted to a prior course of dealing. The FTC advances this argument even though at the time that Qualcomm made this commitment, Qualcomm never actually licensed its patents to competing chip makers. Indeed, Qualcomm never did license these patents to competitors, the company only ever promised to do so. If that promise counts as prior dealing, then Qualcomm’s subsequent refusal to carry out its promise and license its patents would constitute a termination of a prior dealing. And, argues the FTC, that prior dealing was notionally profitable because Qualcomm’s commitment included a promise only to license at fair, reasonable and nondiscriminatory (FRAND) terms, which means profitable terms.

The FTC’s argument is obviously an abuse of the concept of a termination of a prior profitable course of dealing. Because a promise to deal profitably in the future is not in fact a prior profitable course of dealing. They are different things. But that does not mean that the FTC should lose, only that the rule toward which the Supreme Court gestured in Aspen Skiing and Trinko is not a great rule, and should not be treated as hard and fast by the courts.

Where, as in the Qualcomm case, the essentiality of a patent to competitors results from the actions of a standards body and not from the innovative superiority of the patented invention, and the firm’s refusal to license did not improve the product as an economic matter, and therefore must have harmed consumers, the courts must hold the defendant liable for monopolization in violation of the Sherman Act.

The courts can continue to treat a termination of a prior profitable course of dealing as suggestive of the potential for consumer harm in a refusal to deal. But when the courts encounter a case in which the essentiality of a patent arises by administrative fiat, rather than market forces, they shouldn’t kill the case on account of the absence of a termination of a prior profitable course of dealing.

Which is why the district court got this case right, and the Ninth Circuit should affirm.

(The FTC has also tried to get around the termination of a prior profitable course of dealing requirement by arguing that Qualcomm’s refusal to license directly to cell phone makers is a separate antitrust violation, distinct from Qualcomm’s refusal to license to rival chip makers. While there is some basis in law for treating this conduct (which amounts to tying) as an independent basis for liability for monopolization, I see it as just an indirect way of refusing to sell to rival chip makers, one to which the termination of a prior profitable course of dealing requirement could apply. Licensing directly to cell phone makers is equivalent to having Qualcomm license to chip makers and then having the chip makers ask cell phone makers to pay a portion of the purchase price of their chips directly to Qualcomm. A willingness on the part of Qualcomm to license either directly to cell phone makers or to rival chip makers would amount to a willingness to supply an input essential to rival chip makers’ success, and Qualcomm’s refusal to license through both channels therefore amounts to a refusal to supply an essential input to competitors. This behavior should count, either way, as a refusal to deal with competitors, and be considered under the legal rules governing such refusals.)