Liu et al.’s paper trying to connect market concentration to low interest rates reflects everything that’s good and bad about economics.

The Good Is the Story

The good is that the paper tells a plausible story about why the current era’s low interest rates might actually be the cause of the low productivity growth and increasing markups we are observing, as well as the increasing market concentration we might also be observing.

The story is that low interest rates encourage investment in innovation, but investment in innovation paradoxically discourages competition against dominant firms, because low rates allow dominant firms to invest more heavily in innovation in order to defend their dominant positions.

The result is fewer challenges to market dominance and therefore less investment in innovation and consequently lower productivity growth, increasing markups, and increasing market concentration.

Plausible does not mean believable, however.

The notion that corporate boards across America are deciding not to invest in innovation because they think dominant firms’ easy access to capital will allow them to win any innovation war is farfetched, to say the least.

“Gosh, it’s too bad rates are so low, otherwise we might have a chance to beat the iPhone,” said one Google Pixel executive to another never.

And it’s a bit too convenient that this monopoly-power-based explanation for two of the major stylized facts of the age–low interest rates and low productivity growth–would come along at just the moment when the news media is splashing antitrust across everyone’s screens for its own private purposes.

But plausibility is at least helpful to the understanding (as I will explain more below), and the gap between it and believability is not the bad part of economics on display in Liu et al.

The Bad Is the General Equilibrium

The bad part is the the authors’ general equilibrium model.

They think they need the model to show that the discouragement competitors feel at the thought of dominant firms making large investments in innovation to thwart them outweighs the incentive that lower interests rates give competitors, along with dominant firms, to invest in innovation.

If not, then competitors might put aside their fears and invest anyway, and productivity growth would then increase anyway, and concentration would fall.

Trouble is, no general equilibrium model can answer this question, because general equilibrium models are not themselves even approximately plausible models of the real world, and economists have known this since the early 1970s.

Intellectually Bankrupt for a While Now

Once upon a time economists thought they could write down a model of the economy entire. The model they came up with was built around the concept of equilibrium, which basically meant that economists would hypothesize the kind of bargains that economic agents would be willing to strike with each other–most famously, that buyers and sellers will trade at a price at which supply equals demand–and then show how resources would be allocated were everyone in the economy in fact to trade according to the hypothesized bargaining principles.

As Frank Ackerman recounts in his aptly-titled assessment of general equilibrium, “Still Dead After All These Years: Interpreting the Failure of General Equilibrium Theory,” trouble came in the form of a 1972 proof, now known as the Sonnenschein-Mantel-Debreu Theorem, that there is never any guarantee that actual economic agents will bargain their way to the bargaining outcomes–the equilibria–that form the foundation of the model.

In order for buyers and sellers of a good to trade at a price the equalizes supply and demand, the quantity of the good bid by buyers must equal the quantity supplied at the bid price. If the price doesn’t start at the level that equalizes supply and demand–and there’s not reason to suppose it should–then the price must move up or down to get to equilibrium.

But every time price moves, it affects the budgets of buyers and sellers, who much then adjust their bids across all the other markets in which they participate, in order to rebalance their budgets. But that in turn means prices in the other markets must change to rebalance supply and demand in those markets.

The proof showed that there is no guarantee that the adjustments won’t just cause prices to move in infinite circles, an increase here triggering a reduction there that triggers another reduction here that triggers an increase back there, and so on, forever.

Thus there is no reason to suppose that prices will ever get to the places that general equilibrium assumes that they will always reach, and so general equilibrium models describe economies that don’t exist.

Liu et al.’s model describes an economy with concentrated markets, so it doesn’t just rely on the supply-equals-demand definition of equilibrium targeted by the Sonnenschein-Mantel-Debreu Theorem, a definition of equilibrium that seeks to model trade in competitive markets. But the flaw in general equilibrium models is actually even greater when the models make assumptions about bargaining in concentrated markets.

We can kind-of see why, in competitive markets, an economic agent would be happy to trade at a price that equalizes supply and demand, because if the agent holds out for a higher price, some other agent waiting in the wings will jump into the market and do the deal at the prevailing price.

But in concentrated markets, in which the number of firms is few, and there is no competitor waiting in the wings to do a deal that an economic agent rejects, holding out for a better price is always a realistic option. And so there’s never even the semblance of a guarantee that whatever price the particular equilibrium definition suggests should be the one at which trade takes place in the model would actually be the price upon which real world parties would agree. Buyer or seller might hold out for a better deal at a different price.

Indeed, in such game theoretic worlds, there is not even a guarantee that any deal at all will be done, much less a deal at the particular price dictated by the particular bargaining model arbitrarily favored by the model’s authors. Bob Cooter called this possibility the Hobbes Theorem–that in a world in which every agent holds out for the best possible deal, one that extracts the most value from others, no deals will ever get done and the economy will be laid to waste.

The bottom line is that all general equilibrium models, including Liu et al.’s, make unjustified assumptions about the prices at which goods trade, not to mention whether trade will take place at all.

But are they at least good as approximations of reality? The answer is no. There’s no reason to suppose that they get prices only a little wrong.

That makes Liu et al.’s attempt to use general equilibrium to prove things about the economy something of a farce. And their attempt to “calibrate” the model by plugging actual numbers from the economy into it in order to have it spit out numbers quantifying the effect of low interest rates on productivity, absurd.

If general equilibrium models are not accurate depictions of the economy, then using them to try to quantify actual economic effects is meaningless. And a reader who doesn’t know better might might well come away from the paper with a false impression of the precision with which Liu et al. are able to make their economic arguments about the real world.

So Why Is It Still Used?

But if general equilibrium is a bad description of reality, why do economists still use it?

It Creates a Clear Pecking Order

Partly because solving general equilibrium models is hard, and success is clearly observable, so keeping general equilibrium models in the economic toolkit provides a way of deciding which economists should get ahead and be famous: namely, those who can work the models.

By contrast, lots of economists can tell plausible, even believable, stories about the world, and it can take decides to learn which was actually right, making promotion and tenure decisions based on economic stories a more fraught, and necessarily political, undertaking.

Indeed, it is not without a certain amount of pride that Liu et al. write in their introduction that

[w]e bring a new methodology to this literature by analytically solving for the recursive value functions when the discount rate is small. This new technique enables us to provide sharp, analytical characterizations of the asymptotic equilibrium as discounting tends to zero, even as the ergodic state space becomes infi�nitely large. The technique should be applicable to other stochastic games of strategic interactions with a large state space and low discounting.

Ernest Liu et al., Low Interest Rates, Market Power, and Productivity Growth 63 (NBER Working Paper, Aug. 2020).

Part of the appeal of the paper to the authors is that they found a new way to solve the particular category of models they employ. The irony is that technical advances of this kind in general equilibrium economics are like the invention of the coaxial escapement for mechanical watches in 1976: a brilliant advance on a useless technology.

It’s an Article of Faith

But there’s another reason why use of general equilibrium persists: wishful thinking. I suspect that somewhere deep down economists who devote their lives to these models believe that an edifice so complex and all-encompassing must be useful, particularly since there are no other totalizing approaches to mathematically modeling the economy on offer.

Surely, think Liu et al., the fact that they can prove that in a general equilibrium model low interest rates drive up concentration and drive down productivity growth must at least marginally increase the likelihood that the same is actually true in the real world.

The sad truth is that, after Sonnenschein-Mantel-Debreu, they simply have no basis for believing that. It is purely a matter of faith.

Numeracy Is Charismatic

Finally, general equilibrium persists because working really complicated models makes economics into a priesthood. The effect is exactly the same as the effect that writing had on an ancient world in which literacy was rare.

In the ancient world, reading and writing were hard and mysterious things that most people couldn’t do, and so they commanded respect. (It’s not an accident that after the invention of writing each world religion chose to idolize a book.) Similarly, economics–and general equilibrium in particular–is something really hard that most literate people, indeed, even most highly-educated people and even most social scientists, cannot do.

And so it commands respect.

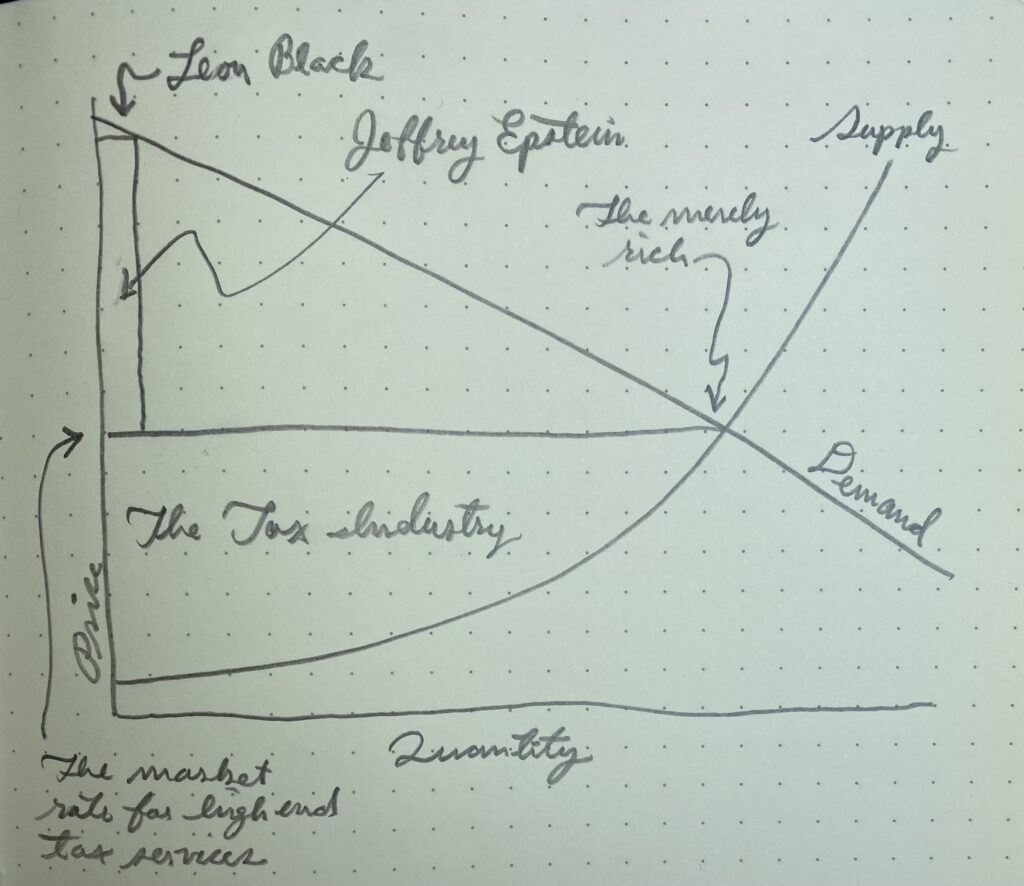

I have long savored the way the mathematical economist gives the literary humanist a dose of his own medicine. The readers and writers lorded it over the illiterate for so long, making the common man shut up because he couldn’t read the signs. It seems fitting that the mathematical economists should now lord their numeracy over the merely literate, telling the literate that they now should shut up, because they cannot read the signs.

It is no accident, I think, that one often hears economists go on about the importance of “numeracy,” as if to turn the knife a bit in the poet’s side. Numeracy is, in the end, the literacy of the literate. But schadenfreude shouldn’t stop us from recognizing that general equilibrium has no more purchase on reality than the Bhagavad Gita.

To be sure, economists’ own love affair with general equilibirium is somewhat reduced since the Great Recession, which seems to have accelerated a move from theoretical work in economics (of which general equilibrium modeling is an important part) to empirical work.

But it’s important to note here that economists have in many ways been reconstituting the priesthood in their empirical work.

For economists do not conduct empirics the way you might expect them to, by going out and talking to people and learning about how businesses function. Instead, they prefer to analyze data sets for patterns, a mathematically-intensive task that is conveniently conducive to the sort of technical arms race that economists also pursue in general equilibrium theory.

If once the standard for admission to the cloister was fluency in the latest general equilibrium techniques, now it is fluency in the latest econometric techniques. These too overawe non-economists, leaving them to feel that they have nothing to contribute because they do not speak the language.

Back to the Good

But general equilibrium’s intellectual bankruptcy is not economics’ intellectual bankruptcy, and does not even mean that Liu et al.’s paper is without value.

For economic thinking can be an aid to thought when used properly. That value appears clearly in Liu et al.’s basic and plausible argument that low interest rates can lead to higher concentration and lower productivity growth. Few antitrust scholars have considered the connection between interest rates and market concentration, and the basic story Liu et al. tell give antitrusters something to think about.

What makes Liu et al.’s story helpful, in contrast to the general equilibrium model they pursue later in the paper, is that it is about tendencies alone, rather than about attempting to reconcile all possible tendencies and fully characterize their net product, as general equilibrium tries to do.

All other branches of knowledge undertake such simple story telling, and indeed limit themselves to it, and so one might say that economics is at its best when it is no more ambitious in its claims than any other part of knowledge.

When a medical doctor advises you to reduce the amount of trace arsenic in your diet, he makes a claim about tendencies, all else held equal. He does not claim to account for the possibility that reducing your arsenic intake will reduce your tolerance for arsenic and therefore leave you unprotected against an intentional poisoning attempt by a colleague.

If the doctor were to try to take all possible effects of a reduction in arsenic intake into account, he would fail to provide you with any useful knowledge, but he would succeed at mimicking a general equilibrium economist.

When Liu et al. move from the story they tell in their introduction to their general equilibrium model, they try to pin down the overall effect of interest rates on the economy, accounting for how every resulting price change in one market influences prices in all other markets. That is, they try in a sense to simulate an economy in a highly stylized way, like a doctor trying to balance the probability that trace arsenic intake will give you cancer against the probability that it will save you from a poisoning attempt. Of course they must fail.

When they are not deriding it as mere “intuition,” economists call the good economics to which I refer “partial equilibrium” economics, because it doesn’t seek to characterize equilibria in all markets, but instead focuses on tendencies. It is the kind of economics that serves as a staple for antitrust analysis.

What will a monopolist’s increase in price do to output? If demand is falling in price–people buy less as price rises–then obviously output will go down. And what will that mean for the value that consumers get from the product? It must fall, because they are paying more, so we can say that consumer welfare falls.

Of course, the higher prices might cause consumers to purchase more of another product, and economies of scale in production of that other product might actually cause its price to fall, and the result might then be that consumer welfare is not reduced after all.

But trying to incorporate such knock-on effects abstractly into our thought only serves to reduce our understanding, burying it under a pile of what-ifs, just as concerns about poisoning attempts make it impossible to think clearly about the health effects of drinking contaminated water.

If the knock-on effects predominate, then we must learn that the hard way, by acting first on our analysis of tendencies. And even if we do learn that the knock-on effects are important, we will not respond by trying to take all effects into account general-equilibrium style–for that would gain us nothing but difficulty–but instead we will respond by flipping our emphasis, and taking the knock-on effects to be the principal effects. We will assume that the point of ingesting arsenic is to deter poisoning, and forget about the original set of tendencies that once concerned us, namely, the health benefits of avoiding arsenic.

Our human understanding can do no more. But faith is not really about understanding.

(Could it be that general equilibrium models are themselves just about identifying tendencies, showing, perhaps, that a particular set of tendencies persists even when a whole bunch of counter-effects are thrown at it? In principle, yes. Which is why very small general equilibrium models, like the two-good exchange model known as the Edgeworth Box, can be useful aids to thought. But the more goods you add in, and the closer the model comes to an attempt at simulating an economy–the more powerfully it seduces scholars into “calibrating” it with data and trying to measure the model as if it were the economy–the less likely it is that the model is aiding thought as opposed to substituting for it.)