President Biden’s Executive Order on Promoting Competition in the American Economy does a great job of targeting a range of business practices across the economy that harm workers and consumers.

But the order—and the fact sheet accompanying it—also highlight how much wishful thinking is currently going into the contemporary progressive romance with competition as an economic cure-all.

The fact sheet declares that economists have found a link between competition and inequality, even though whether a link exists remains the most important open question in antitrust economics today and the subject of much ongoing debate. And despite the competition rhetoric, most of the order is actually about consumer protection or price regulation by other means, not competition.

Wishful Thinking about Competition and Inequality

Anyone who has been following the unresolved debate over the existence of a link between competition and inequality is going to be surprised to learn from President Biden’s fact sheet that “[e]conomists find that as competition declines . . . income [and] wealth inequality widen.”

The surprised might include Thomas Piketty, the dean of the contemporary economic study of wealth inequality, who has observed that the fundamental cause of inequality “has nothing to do with market imperfections and will not disappear as markets become freer and more competitive.”

But it might also be news to the authors cited by the fact sheet itself.

Follow the first of the quoted links and you get to a paper that connects the decline in labor’s share of GDP (a proxy for inequality) to rising markups (firms charging higher prices relative to their costs), but not to a decline in competition.

The author is careful not to link rising markups to a decline in competition because increases in markups have two potential causes, not one: monopoly power and scarcity power—as I have highlighted in a recent paper.

That is, firms can obtain the power to jack up prices by excluding competitors and achieving monopoly power, or they can do it by making better products than everyone else (or the same products at lower cost), in which case even the price prevailing in a perfectly competitive market will represent a markup over cost.

The great open question of contemporary antitrust economics is whether the evidence of an increase in markups in recent years is evidence of monopoly markups or scarcity markups. As Amit Zac has pointed out to me, this is the essence of the disagreement between the work of De Loecker et al. (monopoly markups) on the one hand and the work of Autor et al. (scarcity markups) on the other.

The point is: this is an unresolved question. Economists haven’t “found” a connection between declining competition and contemporary increases in inequality. They haven’t even found a connection between declining competition and contemporary increases in markups. They’re still looking.

But you wouldn’t know that from the fact sheet.

Follow the second of those links and the support is equally weak. The title of the cited article, “Inequality: A Hidden Cost of Market Power,” would no doubt appeal to a fact sheet writer fishing Google for quick cites. But the paper itself could not be more timid about its conclusions, telling readers that it does no more than to “illustrate[] a mechanism by which market power can contribute to unequal economic outcomes” and warning that “[a]lternative models and assumptions may yield different results.”

The authors have good reason to be timid, because the paper’s attempt to distinguish between monopoly markups and scarcity markups extends no further than this: “we attempt to compare actual mark-ups with the lowest sector specific mark-ups observed across countries, in order to estimate an unexplained or excess mark-up.”

So: find the lowest markups in an industry, assume they are scarcity markups, and attribute any markups you find that exceed them to monopoly.

Not exactly convincing, as the authors themselves seem to telegraph—which is why the character of the higher markups we are observing today very much remains an open question.

Highlighting Antimonopolism’s Intellectual Deficit

The last revolution in antitrust policy happened in the 1970s, and however one might feel about the path it beat toward less antitrust enforcement, there is one thing one must grant: it carried the day as an intellectual matter.

You can’t read the book of papers produced by the epochal Airlie House conference and not get the impression that the Chicago Schoolers really got the best of the old antitrust establishment on the plane of ideas. I once asked Mike Scherer, who carried the banner for the old pro-enforcement establishment more than anyone at that conference, why he comes across as so timid in the dialogues reproduced in that book.

His answer: Chicago had convinced him, too.

The current inflection point in antitrust has not been built on anything like that level of intellectual consensus. I have argued elsewhere that this is because the current movement didn’t need to win the academy to achieve liftoff, as Chicago did. The current movement got its thrust instead from a highly sympathetic press, which has a competitive interest in unleashing a reinvigorated antitrust on its nemeses, the Tech Giants.

It is a symptom of contemporary antimonopolism’s intellectual deficit that our new, self-consciously reality-based administration can go to war against monopoly only by passing off economic conjecture as economic fact.

Did Golden-Age Antitrust Drive Postwar Economic Growth and Save Consumers “Billions”?

Before moving on from the order’s wishful thinking, I can’t help but also mention the fact sheet’s claim that mid-20th-century antitrust “saved consumers billions in today’s dollars and helped unleash decades of sustained, inclusive economic growth.”

Was mid-20th-century antitrust enforcer Thurman Arnold responsible for America’s 2% annual growth rate from the 1950s to the 1970s?

The press release doesn’t cite any economic study taking that position—because there is none. But there are plenty that think those twenty years of 2% growth had something to do with the nation’s return to the peacetime production possibilities frontier after nearly two decades of depression and war.

And did mid-20th century antitrust really save consumers “billions?” You might be forgiven for thinking that link leads to a recent economic study. Instead, it is to a set of figures, released by Thurman Arnold himself, that are cited by legal historian Spencer Weber Waller as possible exaggerations. For example, Waller: “[Arnold’s] case against the milk industry in Chicago supposedly produced $10,000,000 a year in consumer savings” (emphasis mine).

All the figures cited by Waller do probably add up to billions in today’s dollars. But Waller cited them as evidence that Arnold knew how to use hyperbole to win political support for his antitrust campaigns.

Not that the Biden Administration would be doing the same thing.

Competition as Price Regulation by Other Means

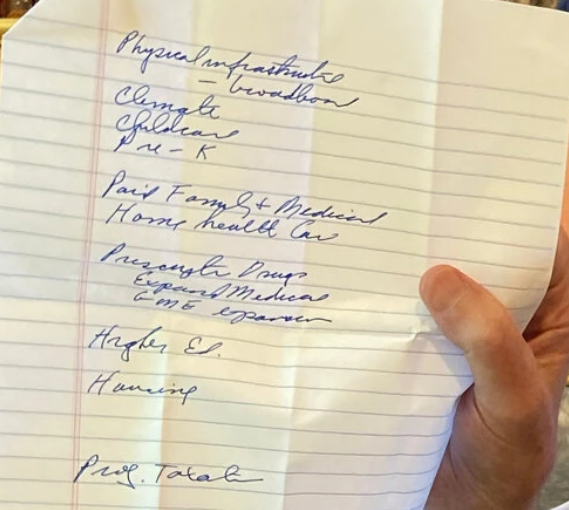

But what about the order itself? Here’s where things really get interesting. For despite the rhetoric little of it is actually about competition: it is, amazingly, largely about price regulation and consumer protection instead.

Why? Because the competition business and the inequality business are two very different things; and no matter how hard you tell yourself you are doing competition policy, if you’re trying to equalize wealth, you’re going to end up doing something else.

To see why the order is mostly about price regulation, consider that competition really has two virtues, one more important than the other. The smaller virtue is that competition can reduce prices. The greater virtue is that competition promotes innovation, which is the principal driver of economic growth and benefits to workers and consumers alike.

The reason competition’s effect on prices is a lesser virtue is that competition is wasteful. It means duplication of management and often diseconomies of scale. As I have argued at length elsewhere, if you want to get price down it’s far less expensive simply to order lower prices than to try to jerryrig markets into producing them through unregulated competition.

Antitrust gets this, and so it does not actually prohibit the charging of high prices. Antitrust is much more interested in prohibiting conduct aimed at excluding competitors from markets, because this keeps out the sort of innovative challengers that are responsible for the link between competition and innovation.

The striking thing about Biden’s order is that it is mostly aimed at promoting the first kind of competition—competition meant to lower prices—rather than the second.

Which makes it price regulation by other means. Let’s consider some of the initiatives contained in the order.

Canadian Drugs

The order calls for lowering prescription drug prices by importing drugs from Canada. The thing is: the drugs imported from Canada will be the same as drugs sold in America, only cheaper, which means that the only competition this will create will be between the same products sold at different prices on different sides of the border.

Promoting competition between iterations of the same product produced by a single producer isn’t going to promote innovation. It’s just price regulation by other means.

And wasteful means at that. There’s a reason why Canada has lower drug prices than the U.S., and it’s not because there’s more competition in Canada—a lot of Canadian drugs come from America in the first place. It’s because Canada regulates drug prices directly.

So why can’t we just do that, too, instead of sending American drugs north to be price regulated so that we can bring them back down south at lower prices?

Because, I guess, that wouldn’t sound like a competition policy solution, and progressives today are convinced that competition cures all.

Generic Drugs

The order also simultaneously calls for more antitrust enforcement against “pay-for-delay” drug patent settlements and “more support for generic and biosimilar drugs.”

As in the case of drugs from Canada, competition from generic drugs doesn’t promote innovation. Generics are, by definition, copies of preexisting drugs; generic drug companies don’t invent new drugs, they just strive to bring old ones to market at low prices. So generic competition is just price regulation by other means, and particularly futile and inefficient means at that.

For branded drug companies use pay-for-delay settlements to undermine generic competition, and enforcers have wasted untold hours litigating to stop them, to only modest effect. Plus, forty years after Congress embraced generic competition with the Hatch-Waxman Act, we still have a drug price problem.

That makes an order telling the agencies to stop pay-for-delay and to promote generic competition at the same time more than a little odd. It is like telling a fireman to pump harder and stop more leaks. It might be time to find a different hose.

If Congress wants to get drug prices down, the easiest way to do it would be to follow the Canadians and, you know, order drug prices down, rather than trying to manage the Herculean task of creating and maintaining a competitive generic drug market. The Biden Administration should call for that.

But competition cures all.

The Right to Repair

The order also calls for protecting the right of buyers to repair a host of items from cell phones to tractors.

Now, one can imagine that competition between repair shops might lead to innovation. But it will be innovation in repairs, which is not going to do much to raise living standards. The innovation that matters is not in repairs but in the design of the products being repaired.

Opening products up to third-party repairs isn’t really about competition at all, therefore, but about price regulation by other means.

And not regulation of the price of repairs, but rather of the price of the product to be repaired. The Biden Administration probably believes that making products reparable will drive down the all-in price that buyers pay for the products, because buyers will be able to avoid paying high repair fees to manufacturers, or will be able to go for a longer period before having to replace the item with a new one.

But if manufacturers are able to extract extra revenues from their buyers by charging them for repairs today, what’s to stop them from simply raising their up-front prices to compensate for lower revenues on repairs tomorrow?

If the Biden Administration thinks cell phones and tractors are too expensive, a better way to actually reduce the amount people pay for these products would be to order manufacturers to charge lower all-in prices for them.

But competition cures all.

Small Business Procurement

The fact sheet says that the order will “[i]ncrease opportunities for small businesses by directing all federal agencies to promote greater competition through their procurement and spending decisions.”

But “competition” here means the opposite of what we normally mean. It means that the firm offering the best products at the lowest prices shouldn’t get the contract; the smallest firm should get it instead, even if it offers shoddy products at high prices.

This is regulation of the price paid by government for goods and services by other, deeply inefficient means.

Here’s a better way to redistribute wealth from taxpayers to small businesses that can’t make it in the market: just write their owners checks to stay home. That way the (presumably) poor get their money without the federal government having buy anything but the best.

But competition—or its semblance—cures all.

Protecting Third-Party Sellers on Amazon

The order also directs the FTC to create rules for “internet marketplaces” and the fact sheet suggests that the rules should prevent Amazon from copying the products of third-party sellers.

As the use of generic competition to tame drug prices suggests, the sort of competition that comes from copying is primarily about getting prices down, rather than innovation. If Amazon wanted to beat its third-party sellers by innovating, it wouldn’t create close matches of their products, but rather something new. By selling an identical product, Amazon instead places all the competitive pressure on price.

So we can understand rules preventing Amazon from copying as attempts to drive the price of goods sold on Amazon’s ecommerce platform up, presumably to redistribute wealth from consumers to third-party sellers. Such rules are, in other words, price regulation by other means.

Because the rules would drive prices up, they are the least consumer-friendly initiative described in the fact sheet (unless one expects Amazon to respond by competing more with its third-party sellers based on innovation).

But precisely because the rules seek to drive prices up rather than down—to squelch duplicative and wasteful competition between Amazon and third-party sellers rather than to promote it—they are also the order’s least inefficient example of price regulation by other means.

But they represent price regulation by other means all the same.

Non-Competes

According to the fact sheet, the order “encourages the FTC to ban or limit non-compete agreements.”

Non-compete agreements in high-skilled jobs are associated with higher wages, suggesting that at the high end they help firms invest in their employees, and that investment, in leading to new skills and abilities, counts as a kind of innovation in human resources.

But the fact sheet is interested in the application of non-competes at the low end: to “tens of millions of [presumably ordinary] Americans—including those working in construction and retail . . . .” Here, the evidence suggests that non-competes don’t induce firms to invest more in their employees; they just prevent employees from using outside options to bid up their pay.

A ban on non-competes for ordinary Americans would therefore not have any effect on innovation in worker training, but it would raise wages, making it price regulation by other means.

If we really want to get wages up, of course, the way to do it is to order them up, through initiatives like an increase in the minimum wage. And I get that the Biden Administration indeed also wants to raise the minimum wage.

But that doesn’t make banning non-competes any less price regulation by other means.

Direct Price Regulation

To President Biden’s credit, the order also calls for plenty of direct, and therefore more efficient, price regulation. The remarkable thing is that he does this in a competition order.

The Federal Maritime Commission is to protect American exporters from “exhorbitant” shipping charges. Railroads are to “treat . . . freight companies fairly,” which means charging them lower prices for access to track. The USDA is to “stop[] chicken processors from . . . underpaying chicken farmers.” The FCC is to “limit excessive early termination fees” for internet service. And airlines are to refund fees for wifi or inflight entertainment when the systems are broken—a regulation of the all-in price of a flight.

(Ok, the reason the order doesn’t do more direct price regulation might be that the requisite statutory authority to act in other areas is lacking. But I’m not aware of any Administration calls for Congress to pass new price regulatory legislation, apart from raising the minimum wage and adopting reference pricing in drugs, which latter would apply only to Medicare.)

Consumer Protection

The amount of price regulation—of both the wasteful, competition-mediated sort and of the direct sort—in this order is rivaled only by the amount of consumer protection.

Hospital price transparency is to be fostered, surprise billing condemned. Airline baggage and cancellation fees are to be clearly disclosed. The options in the National Health Insurance Marketplace are to be standardized to facilitate comparison shopping. So too broadband prices.

The common thread to all of these initiatives is that they correct cognitive limitations of consumers that make it difficult for them to find the best, lowest price options on the market, and so leave them poorer. That’s why I class them as consumer protection initiatives, and why they are a good thing.

Consumer protection is competition-adjacent policy—competition does work better, and firms may be more likely to innovate, when consumers have good information about the products offered by competing firms. But the main focus of these initiatives is on empowering consumers to avoid paying out more cash than necessary for goods and services.

Like the price regulation initiatives, it’s directed, ultimately, at the distribution of wealth, not competition. Which is why it is surprising to find so much consumer protection in a competition order.

Unions and Occupational Licensing

The focus on price regulation and consumer protection are a welcome surprise. But the dangers for progressives of confusing these things with competition policy are also on display, for competition is just as likely to be the enemy of equality as it is to be its friend, and it is very easy to lose sight of this when pursuing an equality agenda in competition terms.

Thus in a press release that is already pretty deaf to irony, this takes the cake: “the President encourages the FTC to ban unnecessary occupational licensing restrictions [and] call[s] for Congress to . . . ensure workers have a free and fair choice to join a union . . . .”

Here’s a secret about those “unnecessary licensing restrictions”: they’re state-created unions. The only difference between them and actual unions is that they operate by restricting labor supply, and thereby driving up wages, whereas unions operate by driving wages up, and thereby restricting labor demand. If you’re against occupational licensing because it makes it hard to get a job, you should be against unions, and if you’re in favor of unions because they drive up wages, then you should be in favor of occupational licensing.

The way to minimize mistakes in fighting inequality is to focus on fighting inequality.

Indeed, one cannot help but feel that this order, despite being well-intentioned and expansive, is a sideshow to the real work of fighting inequality that the Administration has undertaken on the tax side. Given the breadth of applicability of the corporate tax—all industries are swept in at once—and the power of the corporate tax to target the proceeds of excessive pricing directly, last week’s agreement of 130 nations to a global minimum corporate tax will likely do far more to divest firms of their markups than anything in today’s order—even were it all implemented as direct price regulation.