The thing that astonishes me about photography is the proof it seems to provide that the past was real. I should never, ever have thought that was the case were it not for photography, my own memories appear so much as dream images to me. They crystallize, like Stendhal’s twigs pulled from the salt mines encrusted with diamonds, until I cannot be sure that they were real. Whatever led scientists to pick, out of the vast spectrum of possible explanations for memory, out of the fairies and gods, the view that memory is just the lasting impression made by light upon the brain?

Category: Miscellany

Two Kinds of Humanism

“American society used to be segregationist before it moved to a multiculturalist model, which is essentially about coexistence of different ethnicities and religions next to one another.”

“Our model is universalist, not multiculturalist,” he said, outlining France’s longstanding insistence that its citizens not be categorized by identity. “In our society, I don’t care whether someone is Black, yellow or white, whether they are Catholic or Muslim, a person is first and foremost a citizen.”

Ben Smith, The President vs. the American Media, N.Y. Times (Nov. 16, 2020).

That is because France still believes in the state. America has never had that problem.

America’s joy today at the success of SpaceX — a private firm — in sending four astronauts on their way to the space station, something the state has been powerless to do for nearly a decade, illustrates this rather nicely.

Place

“When you are a displaced person, and when you are longing for that place and you cannot visit it, that place becomes more than just a stone or mountain, it becomes like a beloved person. You want to kiss it, and lie down on it and feel the energy from the earth.”

Anton Troianovski & Carlotta Gall, After War Between Armenia and Azerbaijan, Peace Sees Winners and Losers Swap Places, N.Y. Times (Nov. 15, 2020).

I wonder how many Americans have such an attachment to place.

We've been here so little time, And move so much, And it's such a big country, With so many different soils.

But some do.

Corporate Law before Capitalism

One forgets that when Blackstone was writing his celebrated Commentaries on the Laws of England in the mid-18th century, business was not the most obvious application of the corporate form.

And so when Blackstone gives a list of types of corporations, he puts the business corporation last:

These artificial persons are called bodies politic, bodies corporate, (corpora corporata) or corporations: of which there is a great variety subsisting, for the advancement of religion, of learning, and of commerce.”

1 William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England 303 (Oxford 2016) (1765).

Blackstone goes on to take, as his primary example of a corporation, not the business corporation, but rather “the case of a college in either of our universities.”

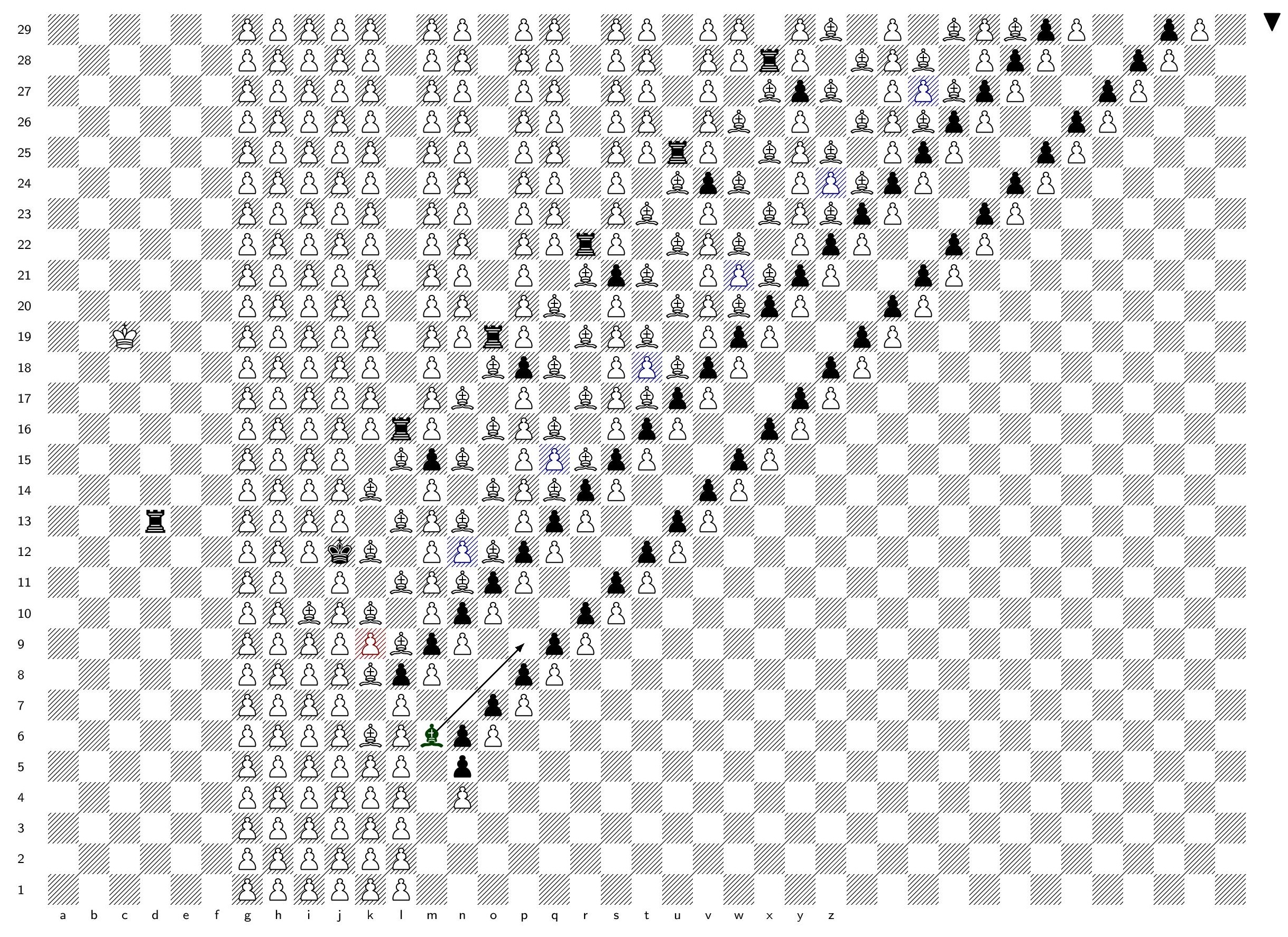

Chess as a Warning

There is a tendency to view the great lesson of chess as being that math-like reasoning works: the systematic thinkers and pattern recognizers among us excel at the game because they can see seven moves ahead, spot traps, and so on.

But that’s the wrong conclusion.

What chess tells us is that if even with fixed rules and an eight-by-eight square board math cannot deliver a key to winning every game–and it looks like it can’t–then imagine how much less useful mechanical thinking would be on the infinity by infinity board with no fixed rules that is life.

Chess has always been an amalgam of systematic behavior that is quite alien to daily life, and strategies and concepts that are much more familiar to us, like daring, care, and luck.

In chess there are the moments when a great systematic mind can see checkmate seven moves ahead. But just as often there are the moments in which several possible moves would open up a near-infinity of possible outcomes and no one can say which is best, both because that depends on what the other player does and because the possible variations are almost too numerous to count.

Sometimes the game lands us on an end branch of the tree of possibilities, and it’s possible to see your way to the blossom on the end, but other times the game lands you on a trunk and the brambles are so dense that you can scarcely see the sky.

When we find ourselves on the end branches, systematic thinking looms large, and we tend to use this as chess’s great lesson for life: find the system! Find mate in seven moves!

But when we find ourselves in the brambles, we call upon the same tools we use in daily life. We think in terms of strategy. Dominate the center of the board. Take the initiative by putting the opponent’s King in check. Pin down important pieces. Defend. Attack. Trust your gut. Victory goes to the bold.

There is in human relationships nothing at all even remotely analogous to mate in seven moves. Sometimes we talk about the relations between great powers as “like a game of chess,” but in truth they never are. The statesman who thinks he can mate his opponent is a dangerous fool, because he will sacrifice sound, human strategy for a system that will inevitably fail.

The closest thing we have to mate in life is the law, which purports at times to be a set of fixed rules that govern all human interactions. But any practicing lawyer will tell you that a bit of politics, or an appeal to heart of a judge, can win a case, even if the letter of the law is against you.

The board of life is so vast, and the pieces so numerous, that we are always, always caught in the brambles, unable to see the sky.

The great success of machine learning in chess represented by AlphaZero, a simple learning algorithm slapped together by Google that went on to beat the best chess computers in the world in dashing style, makes this lesson clear.

The legacy chess computers that AlphaZero beat were systematic thinkers, combining hardcoded programming about the best opening moves with number crunching that would explore possible games emanating from different moves and try to pick the most promising of them.

But AlphaZero is machine learning. Google’s engineers fed it the rules of chess and it played tens of millions of games against itself, creating a map of the best moves in different situations based on whether they ultimately led to a win or a loss.

It takes an approach akin to the approach of the human mind to life: note what seems to work based on experience and then do it when you encounter similar situations in the future. Of course, AlphaZero has a lot more experience to work with, because no one can play forty-four million games with himself in two hours.

The important thing about AlphaZero is that no one, not AlphaZero, not the Google engineers, can identify a winning rule of decision that AlphaZero follows, other than the learning map itself, and that changes as AlphaZero learns. There’s no system in there, other than the learning process, which is really just a method of coping with the richness of experience.

The thing that astonished chess enthusiasts is that AlphaZero plays in a human fashion, making daring sacrifices to achieve positional advantages. Some say it hearkens back to the age of “romantic chess” in the 19th century, before human players became obsessed with systematic play and made the game boring.

The lesson here is not that we have found a mechanical solution to the game. We haven’t: AlphaZero can lose; it’s just better at strategy than anyone else, so it tends to win more often. The lesson is that most of chess is not finding mate in seven moves–otherwise the brute force chess computers would be unbeatable–but rather being very, very good at the the familiar strategies that we use to navigate life: learning from experience, noticing what seems to work.

There’s no doubt that being able to see a few moves ahead helps avoid traps–those mates in seven–and that is what stands out at first about the game to human players.

But it stands out precisely because life is not like that.

In its most extreme form, the state to an American is ‘a bunch of people’, politicians and their officials whom he watches with critical and even distrustful eyes; he sees the state as a powerful instrument that belongs to and is operated by groups of people for their own ends. At the other extreme one finds in Europe the adoration of the state as something majestic, transcendent and even divine (in the tradition of the ‘divine’ emperors of Rome). Nobody expressed this feeling better than the famous philosopher Hegel, who was professor at the Prussian University of Berlin from 1818 to 1831 and wrote: ‘The march of God in the world, that is what the state is. In considering the Idea of the State we must not have our eyes on particular states . . . Instead we must consider the Idea, this actual God, by itself’.

R. C. van Caenegem, An Historical Introduction to Western Constitutional Law 168 (2000).

Eternal Return

He chiseled at the upper left hand corner of the sealed doorway and it fell away. “Can you see anything?” asked C____. “Yes,” he replied.

“How old?”

He angled an elaborate golden headdress through the gap and held it up to the candle. At its center was an object, the size perhaps of a pear, jet black but shimmering somehow in the light, like a pencil lead, cut expertly into a thousand geometric faces.

“Forever,” he replied.

Students forced to learn online are demanding tuition reductions. That is a sign that we still believe that there is such a thing as a just price.

The argument for discounts seems to be that the value of the educational product is less when delivered online, so the price should fall. The implication is that product quality, not market forces, ought to determine price.

Economics rejected just price theory when the world rejected God back at the end of the 19th century. In economics, disillusionment was expressed in the realization that price is determined by supply and demand, not value. Think of a diamond whatever you will. But if supply increases, price will fall. And if demand increases, price will rise. Like everything in a world without God, price is relative.

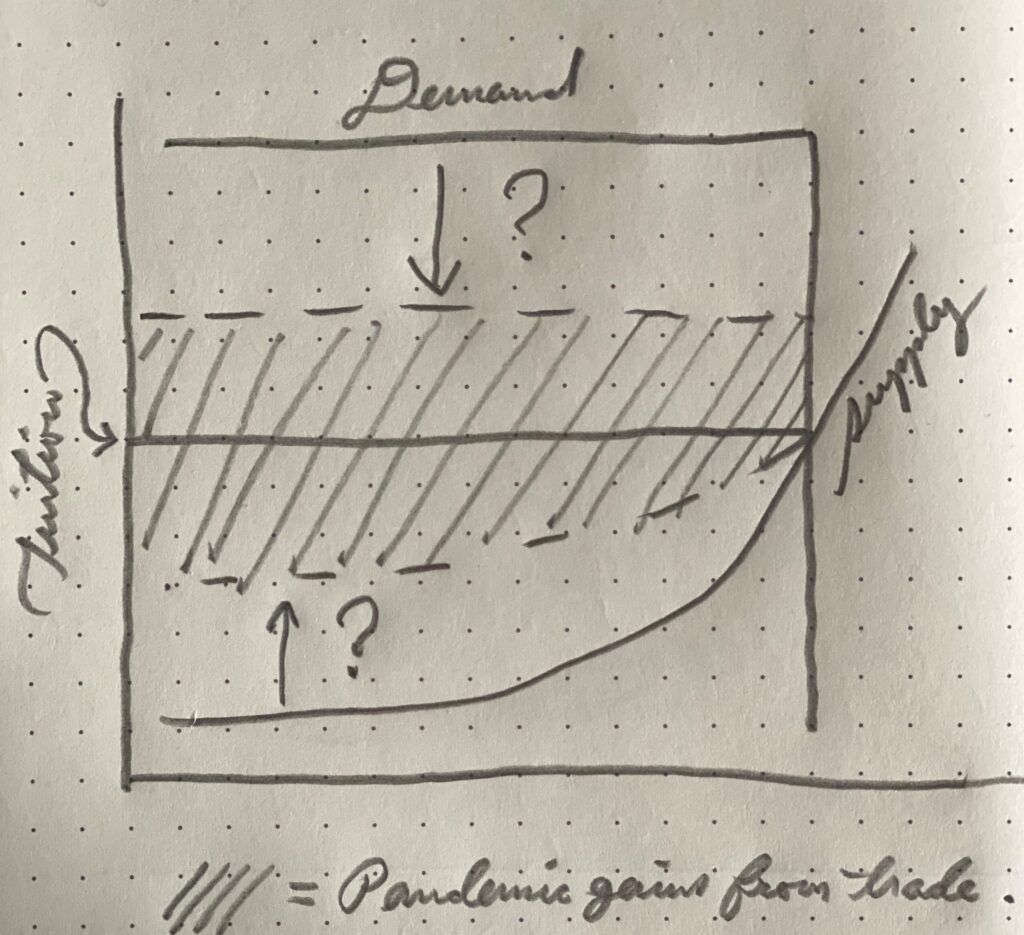

So the economic question posed by the switch to online education is: what’s become of the supply and demand for education in the pandemic?

As an armchair matter, the answer would seem to be: not much.

While some students might choose to forgo school because they believe the quality of online education to be poor, the poor job market suggests that many others will be choosing to return to school. And even if one grants that online teaching is poor in quality, it is more accessible, allowing students who might not have gone to school due to geographic or temporal constraints now to do so. So demand is likely unchanged.

And supply is likely unchanged as well. The poor economy may shutter some schools that were dependent on sports or housing revenues. But the online format allows others to enroll more students from distant markets.

Which suggests that price–tuition–is unlikely to be driven upward or downward by market forces, at least at the industry level.

One complicating factor is competition. The online format could potentially give students more options. It is easier to transfer from a school in California to a school in New York when all that is required is to click on a different Zoom link.

Competition tends to drive prices down. But less so in markets in which the product is highly differentiated. And product differentiation is a huge factor in education, only in education it’s called “reputation.” Students identify with an institution based on legacy status, geographic or sports affiliation, prestige, career networks, and so on, weakening their sensitivity to price in making enrollment choices. The availability of cheap financing (student loans at historically-low interest rates) further reduces the sensitivity to price.

So while competition may put some downward pressure on prices, I wonder if the effect will be large. Schools will likely be able to continue to charge the same tuition rates, despite moving online, because so few students will bail out in response that profits will remain higher than they would be were schools to discount. Indeed, the fact that students are complaining, rather than voting with their feet, suggests that the absence of discounting is not really a dealbreaker for students. It’s more a matter of justice.

But the story does not need to end with market forces. Anger creates social pressure, and that pressure is real.

Although we don’t believe anymore that there is an objectively-verifiable just price, we can still moralize about prices, using the language of progressive law and economics. We can think of the bargaining that takes place between schools and students over tuition as representing a struggle to determine how the two groups share the gains generated by education. To the extent that online education reduces quality, those gains have shrunk. (They have not shrunk at the margin, which is why price is not likely to change much. But they have shrunk inframarginally, reducing the size of the pie.)

In demanding a discount, students are arguing that their share of the gains ought to remain constant. That is, they are arguing that it is not fair to ask them to bear all of the losses associated with constraints placed on the quality of education by the global pandemic, even if market forces dictate that they should.

Schools may reply that their costs have gone up, perhaps because state funding has shrunk, and so they too are suffering losses, leaving students’ share of the gains roughly constant, and therefore just.

So the situation might look something like this:

A.O. Hirschman argued long ago that voice is as powerful a bargaining tool as is exit. Let’s see if that turns out to be true here.

The Reification of Price

Once upon a time, we believed that the law is a real thing in the world, which is why a court could say that a corporation is in Delaware and not in New York.

So too we believed that

the worth of the work may not be easily known; but it has a worth, just as fixed and real as the specific gravity of a substance . . . .

John Ruskin, Unto this Last, and Other Writings 197 (Clive Wilmer, ed. Penguin Classics 2005) (1862).

There are few bargains in which the buyer can ascertain with anything like precision that the seller would have taken no less; — or the seller acquire more than a comfortable faith that the purchaser would have given no more. This impossibility of precise knowledge prevents neither from striving to attain the desired point of greatest vexation and injury to the other, nor from accepting it for a scientific principle that he is to buy for the least and sell for the most possible, though what the real least or most may be he cannot tell.

John Ruskin, Unto this Last, and Other Writings 197 (Clive Wilmer, ed. Penguin Classics 2005) (1862).