There is a tendency to view the great lesson of chess as being that math-like reasoning works: the systematic thinkers and pattern recognizers among us excel at the game because they can see seven moves ahead, spot traps, and so on.

But that’s the wrong conclusion.

What chess tells us is that if even with fixed rules and an eight-by-eight square board math cannot deliver a key to winning every game–and it looks like it can’t–then imagine how much less useful mechanical thinking would be on the infinity by infinity board with no fixed rules that is life.

Chess has always been an amalgam of systematic behavior that is quite alien to daily life, and strategies and concepts that are much more familiar to us, like daring, care, and luck.

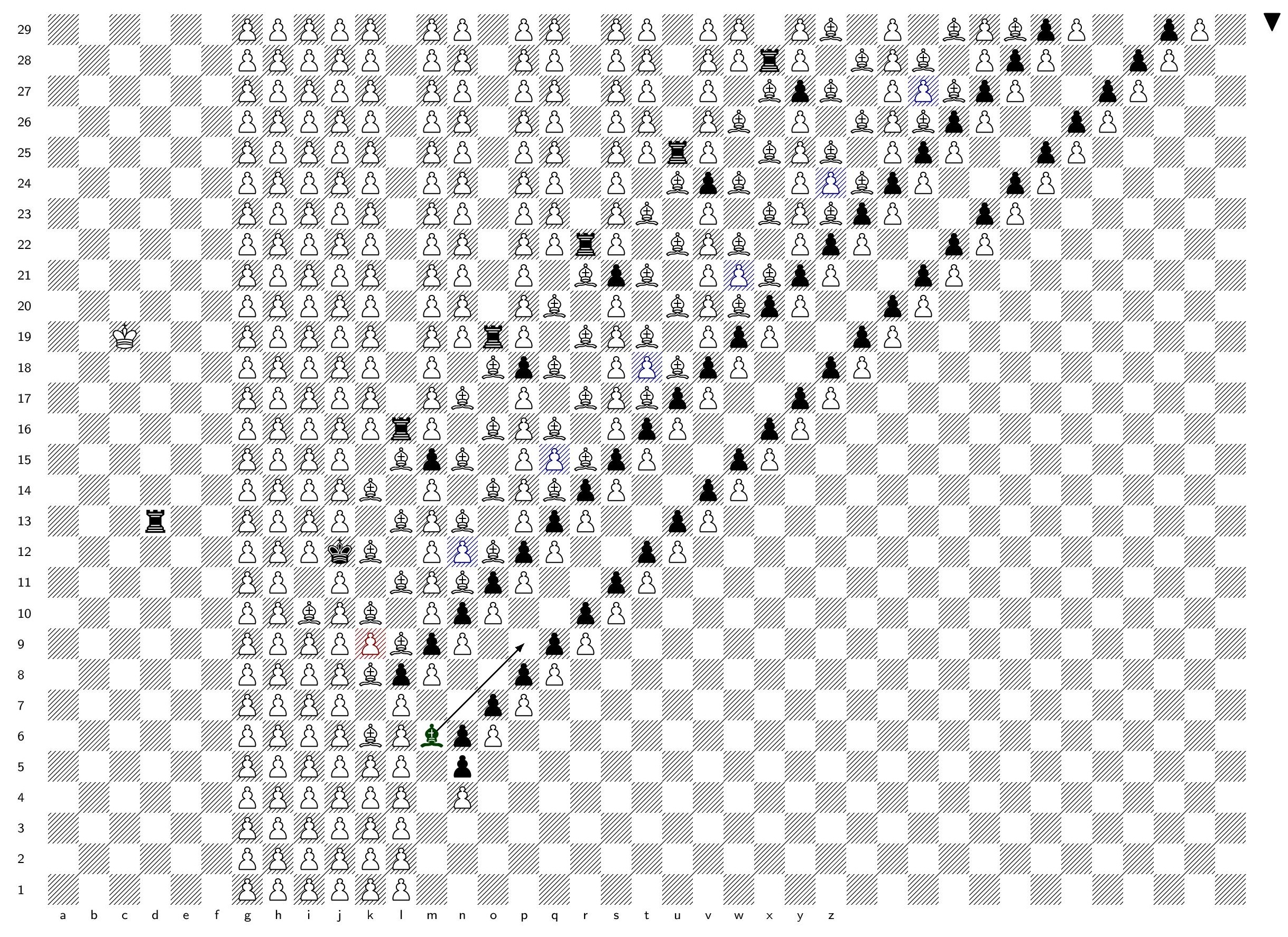

In chess there are the moments when a great systematic mind can see checkmate seven moves ahead. But just as often there are the moments in which several possible moves would open up a near-infinity of possible outcomes and no one can say which is best, both because that depends on what the other player does and because the possible variations are almost too numerous to count.

Sometimes the game lands us on an end branch of the tree of possibilities, and it’s possible to see your way to the blossom on the end, but other times the game lands you on a trunk and the brambles are so dense that you can scarcely see the sky.

When we find ourselves on the end branches, systematic thinking looms large, and we tend to use this as chess’s great lesson for life: find the system! Find mate in seven moves!

But when we find ourselves in the brambles, we call upon the same tools we use in daily life. We think in terms of strategy. Dominate the center of the board. Take the initiative by putting the opponent’s King in check. Pin down important pieces. Defend. Attack. Trust your gut. Victory goes to the bold.

There is in human relationships nothing at all even remotely analogous to mate in seven moves. Sometimes we talk about the relations between great powers as “like a game of chess,” but in truth they never are. The statesman who thinks he can mate his opponent is a dangerous fool, because he will sacrifice sound, human strategy for a system that will inevitably fail.

The closest thing we have to mate in life is the law, which purports at times to be a set of fixed rules that govern all human interactions. But any practicing lawyer will tell you that a bit of politics, or an appeal to heart of a judge, can win a case, even if the letter of the law is against you.

The board of life is so vast, and the pieces so numerous, that we are always, always caught in the brambles, unable to see the sky.

The great success of machine learning in chess represented by AlphaZero, a simple learning algorithm slapped together by Google that went on to beat the best chess computers in the world in dashing style, makes this lesson clear.

The legacy chess computers that AlphaZero beat were systematic thinkers, combining hardcoded programming about the best opening moves with number crunching that would explore possible games emanating from different moves and try to pick the most promising of them.

But AlphaZero is machine learning. Google’s engineers fed it the rules of chess and it played tens of millions of games against itself, creating a map of the best moves in different situations based on whether they ultimately led to a win or a loss.

It takes an approach akin to the approach of the human mind to life: note what seems to work based on experience and then do it when you encounter similar situations in the future. Of course, AlphaZero has a lot more experience to work with, because no one can play forty-four million games with himself in two hours.

The important thing about AlphaZero is that no one, not AlphaZero, not the Google engineers, can identify a winning rule of decision that AlphaZero follows, other than the learning map itself, and that changes as AlphaZero learns. There’s no system in there, other than the learning process, which is really just a method of coping with the richness of experience.

The thing that astonished chess enthusiasts is that AlphaZero plays in a human fashion, making daring sacrifices to achieve positional advantages. Some say it hearkens back to the age of “romantic chess” in the 19th century, before human players became obsessed with systematic play and made the game boring.

The lesson here is not that we have found a mechanical solution to the game. We haven’t: AlphaZero can lose; it’s just better at strategy than anyone else, so it tends to win more often. The lesson is that most of chess is not finding mate in seven moves–otherwise the brute force chess computers would be unbeatable–but rather being very, very good at the the familiar strategies that we use to navigate life: learning from experience, noticing what seems to work.

There’s no doubt that being able to see a few moves ahead helps avoid traps–those mates in seven–and that is what stands out at first about the game to human players.

But it stands out precisely because life is not like that.